On this 16th day of December, Yellow Barn joins the world in celebrating Beethoven's 250th birthday!

To hear his music is to feel human connection, our collective yearning to understand and to be understood, to feel the divine in our humanity. Beethoven's legacy, his gift to us, is a world that bridges emotional alienation, not only with our neighbor, but with ourselves. In this, his music is unwavering. He dares to expect everything of us, even if we doubt. He stakes the apotheosis of his genius on his belief that we can love above all else.

In return, Yellow Barn has formed a new kind of chamber music group! They are a group of visual artists creating a body of work in honor of, and in response to, Beethoven's music and his creative process. Today, their inaugural works appear here for the first time. In coming months, they will begin to appear in public spaces, together with Beethoven's own autographs and music.

It is my pleasure to introduce Beethoven InSight

—Seth Knopp, Artistic Director

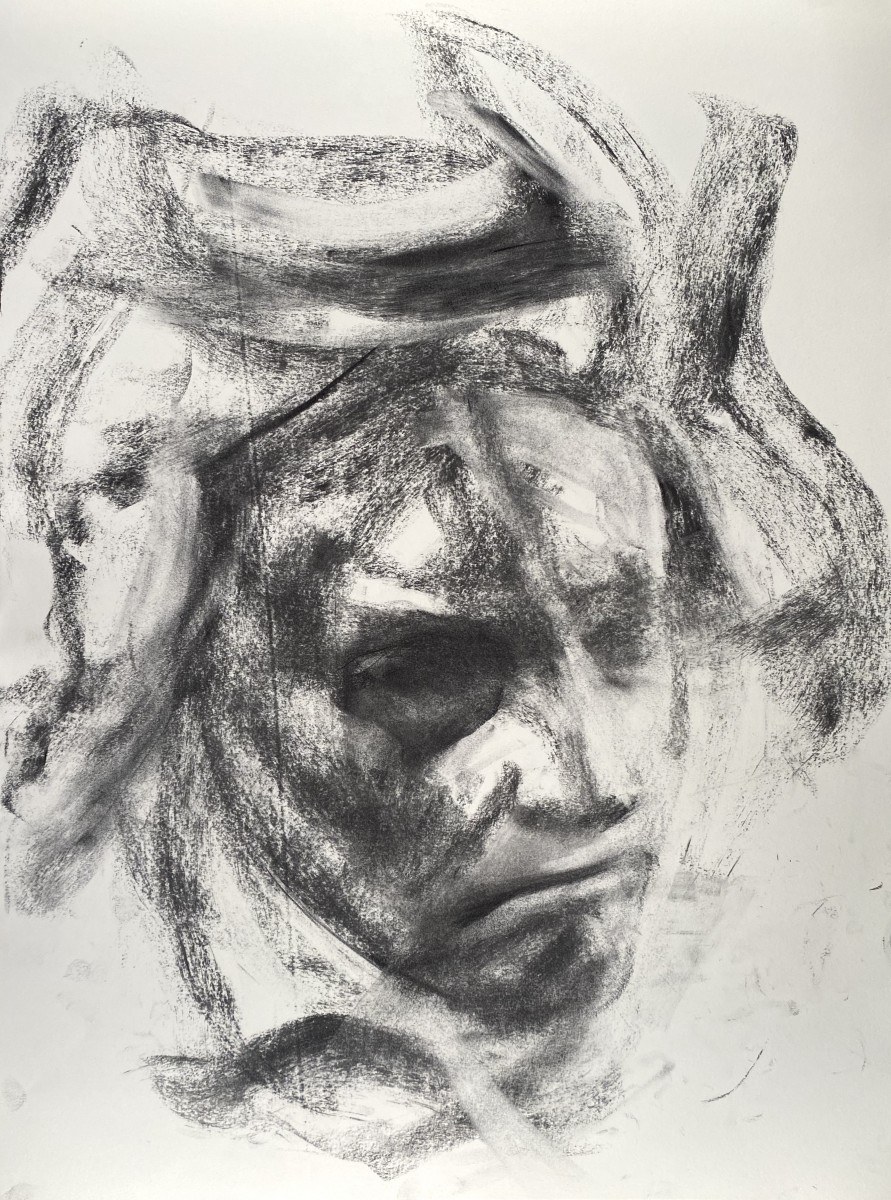

Brian Cohen

charcoal

Rachel Portesi

tintype photograph

Nancy Storrow

pastel

Barbara Garber

paint, colored pencils, and collage

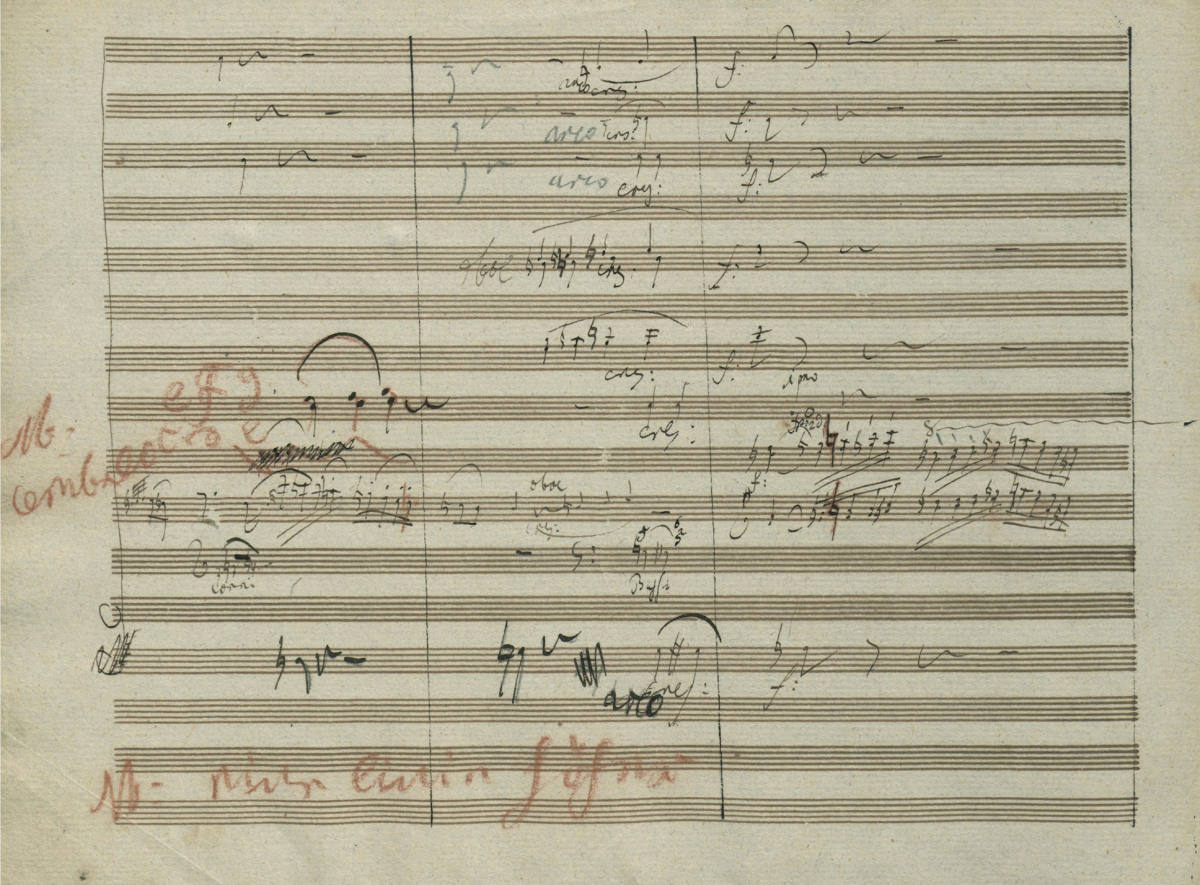

Ludwig van Beethoven

from his autograph manuscript for the Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat Major "Emperor"

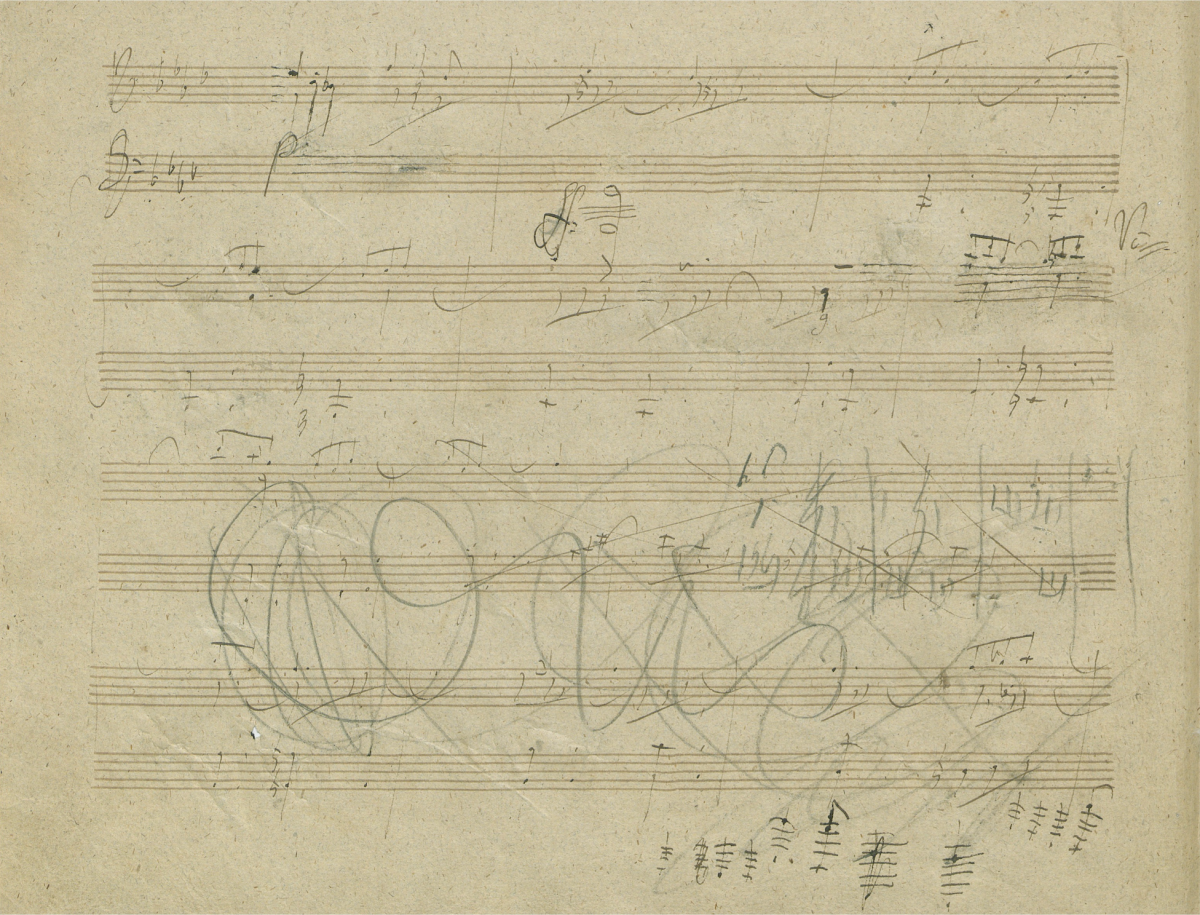

Ludwig van Beethoven

from his autograph manuscript for the Piano Sonata, Op.110

Over the course of the coming months we will be sharing more work from "Beethoven In Sight" artists Brian Cohen, Barbara Garber, Rachel Portesi, and Nancy Storrow, together with garden designer Gordon Hayward, as well as written comments and reflections. Brian Cohen offered the following statement for today's celebration:

Variations on Variations

Beethoven is too big to be contained or depicted. As soon as you look too hard in his direction, you don’t see him anymore, only parts, glimpses, or caricatures. Depictions of Beethoven’s contemporaries seemed to present no such challenges; Haydn is avuncular and senior, like Joe Biden; Schubert, doughy and amiable; Mozart, courtly and boyish (this is a genius?). We know who they are. There are no photographs of Beethoven; he died too soon for that invention, though quite a few contemporary depictions, most second-hand. In representing him, artists seized on and repeated what became the tropes of Romantic genius; the defiant set of his mouth, the unruly hair, the scowl, the tortured brow, the muscular physiognomy, and the cravat and white collar. He is brooding, preoccupied, a little febrile, maybe annoyed or disagreeable (whatever you do, don’t disturb him). Despite the volume of images of the composer, and ceaseless repetition of these clichés, they don’t seem to get us any closer to Beethoven; the images become emblems, standing in for him and replacing him, like a face on a coin.

My original conception for this project was to apprehend aspects or pieces of Beethoven at a time, like medieval depictions of saints — his ear trumpet, his hands, his mouth — as the entire composer is too holy and monumental to show in toto. In my extensive Googling of Beethoven imagery I came across the work of Antoine Bourdelle’s, student of Rodin and teacher of Matisse and Giacometti, a sculptor I knew only tangentially. Bourdelle identified closely with Beethoven (maybe a little too closely, as he wasn’t quite at that level) and created over 80 drawings and sculptures of the composer. In Bourdelle’s work I found animation, energy, depth, inner absorption, fury, and a general lack of restraint absent from other depictions. Bourdelle was inspirational to me and interceded to give me enough distance from Beethoven himself to approach the composer. I think of my response to Bourdelle’s sculptures as variations on variations.

I find my principal challenge is to express all the above qualities of the composer, to avoid the standard models of depiction, and to still have it look like Beethoven. I found his face remarkably labile; too crazy a look in his eyes and he becomes John Belushi; too much five-o’clock shadow and he’s Richard Nixon; too long a face and he’s Leonard Bernstein (which is really not that far off). That mouth, that emblem of defiance, so often suggested by the downward slant of the corners of his mouth and the light on his lower lip, is always tough. I don’t know that I’ve come any closer to who Beethoven is than anyone else, but I’ve found Bourdelle’s work a so far inexhaustible motivation to slip the surly bonds of cliché and touch the face of Beethoven.

—Brian Cohen