Fall 2025 Newsletter

CONTENTS

I. News from the Yellow Barn Garden

II. Reading From Across the Room: From the Stage to the Back Row with Bill Kelly

III. Watch performances from last summer in the Big Barn

DATES OF NOTE

Fall Artist Residencies

Thursday, November 13 at 7:30pm in the Big Barn: Sarah Rommel, cello

Friday, December 12 at 7:30pm in Sun Hill Studio: Seth Knopp, piano; Katherine Yoon, violin; Gerard Flotats, cello

Friday, December 19 at 7:30pm in the Big Barn: Ize Trio (Chase Morrin, piano; George Lernis, percussion; Naseem Alatrash, cello)

View the complete schedule of 2025-26 Artist Residencies

2026 Summer Season

Yellow Barn Festival Concerts: July 10-August 8, 2026

Helena Tulve, Composer in Residence: August 3-8, 2026

Young Artists Program Concerts: June 21-July 3, 2026

News from the YELLOW BARN GARDEN

It has been nearly a year since the first open meeting for the Putney community about our plans for a garden surrounding the Big Barn. Present that evening was garden designer and longtime Putney resident Gordon Hayward. Gordon, who has been a friend of Yellow Barn since its earliest years, generously embraced the process of bringing together our evolving ideas for Yellow Barn "inside out", the initial plan that we created together with landscape architect Chris Donohue at Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, and the ideas and needs expressed by the Putney community at our meetings and in the Town Plan.

Gordon directed the initial uncovering of the land and its trees with arborist Bob Everingham (often introduced by Gordon as a "poet with a chain saw"). The site of the historic Putney Nursery, which was started by George Aiken about 100 years ago, our garden's stature came to light—a sentinel wolf pine in the south field, a grove of poplars near the Putney Co-op, a row of pin oaks near the back entrance, and a circle of evergreens and pachysandra near the library. We set to work clearing the property of invasive species, opening views to the Putney Co-op and Main Street, and keeping the property mowed to promote safe and enjoyable walking.

Immediately, we noticed a difference! People began incorporating our garden into their daily patterns of walking and resting, audience members approached our concerts from new directions, and arrived with open curiosity. "I have lived in Putney for 30 years... How have I never been to Yellow Barn?" was a frequent exclamation, and our hall was full every night of the season.

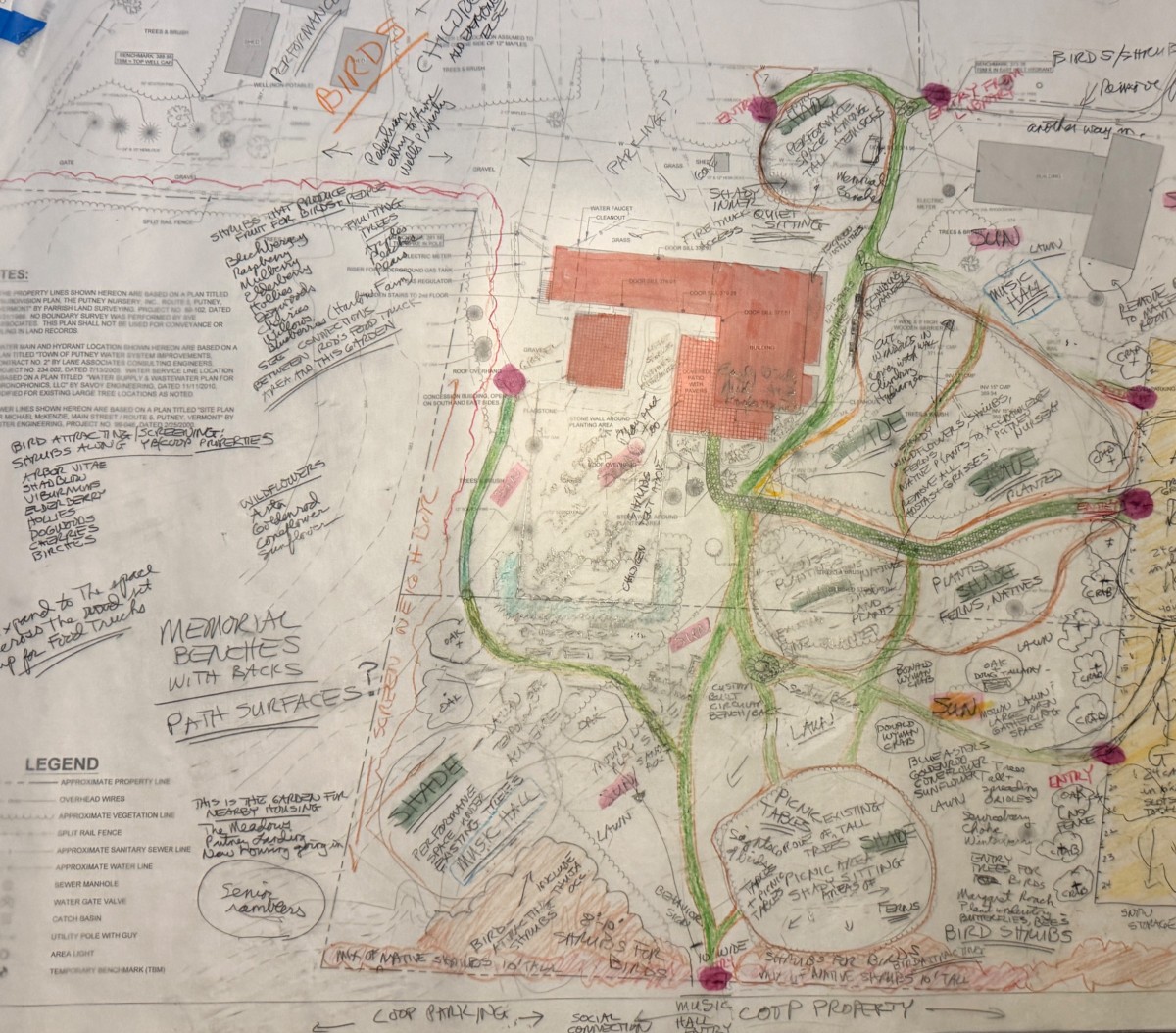

Just before the start of the festival, Gordon presented us with a design that shows how every need could be met on just 3.7 acres of land. It is an extraordinary gift! To see ideas come to life, made beautiful by Gordon's experience and imagination, is both humbling and energizing. His design will now inform our interpretation of Chris Donohue's plan as we strive to create a space that resonates with all of us.

The clearing of the Big Barn property, and this synthesis of ideas, marks the end of Phase I of our garden creation. Between now and the start of the annual audition tour in early January, we will finalize our strategy for building and planting. 14 individuals and families made it possible for us to purchase the Big Barn and to see all that its surrounding property has to offer. In Phase II, everyone will have the opportunity to give the gift of a Yellow Barn Garden to each other.

Gordon Hayward's drawing for the Big Barn property

READING FROM ACROSS THE ROOM:

From the Stage to the Back Row with Bill Kelly

Bill Kelly is a painter, printmaker, and sculptor. He founded Brighton Press, a fine press artists’ book publisher in 1980. Since 1997, he has created hundreds of “Wall Programs” and other art as Yellow Barn’s Artist-in-Residence, and you can find him sitting in the back row of almost every Yellow Barn concert.

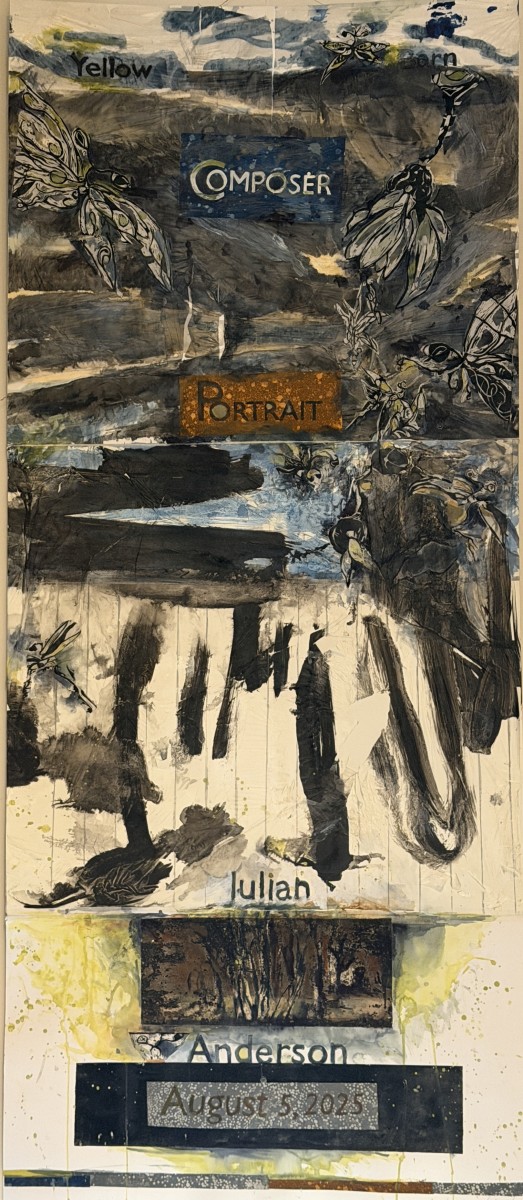

Bill Kelly's wall program from this year's Composer Portrait

"Making a Wall Program"

(Bill Kelly’s advice and ideas sent to all Yellow Barn musicians before they arrive each summer.)

Advice

It is helpful if your poster can be read from across the room.

Keep sight of things that are important in your design. Remember the unifying reason for the poster.

White-out is not a solution to a mistake like it is in typing, hence the visible traces of all of the moves an artist has made and will make.

Most art falls in a range between light and dark. There is no such a thing as black and white in art.

Do not leave dirty brushes in the sink. They are like your instruments; don’t leave them out in the rain or unattended. Make sure to use the right brush for the right job.

Ideas

-Move like a dancer, think like a poet/philosopher.

-Push, but don’t reach. I don’t know how to do this, but I keep trying.

-Don’t aim to please.

-Paint like you mean it.

-Don’t spell Haydn “Hayden” as I did once. It ruined my evening and still haunts me.

-You are part of something big, and a poster is a visual artifact of the moment. Nothing more, nothing less.

In June of 1997, just a few days after my first Yellow Barn summer had begun, I wandered over to the art studio where Bill Kelly taught painting and drawing at the Putney School. Hanging concert programs on the wall above the Yellow Barn stage was a tradition I had inherited, and it made me curious. On concert evenings simple programs were handed out, but I liked the idea that from the audience one could also choose to look through, or next to, the players to get this most basic information.

In my memory, our first meeting was as it has always been since, an easy friendship grounded in art and music. I asked Bill if his class might be interested in sitting in on Yellow Barn rehearsals and then adding “image” to our Wall Program tradition. Bill did not ask anything other than, “When do you want us there?”

These many years later, Bill’s work has become a visual metaphor of what Yellow Barn strives to be, an essential presence when we dream Yellow Barn.

—Seth Knopp

Almost nightly, as a participant at Yellow Barn concerts (by that I mean a participating member of the audience), I wonder at this complicated relationship, between being merely entertained and understanding the complex dynamic that our senses experience. In any given moment, the story that music gives us is in a sense staged, not just performed. Notes may appear static on the score, but sound is an ever-evolving story.

What I see not, I better see—

On any given night we feel familiarity and spontaneity, discord and harmony, surrendering to both sheer beauty and the mystery of the composer’s search. We hear whatever form this arrangement of invention and movement may take through the musician’s voice, and on many evenings, Seth gives us written clues, inspirations in their own original “other” form that often appear along with titles and texts. But the intimacy of scale at Yellow Barn allows us to easily connect with anybody we feel moved to approach, and I take advantage of this by taking it a step further. A conversation with a musician I have only moments ago admired from the audience is spontaneously recorded in my sketchbook:

Pianist Gil Kalish speaking of George Crumb: “George creates atmospheres of wonder. His music deals with the most important aspects of our human experience. Life, death, love and the spirit behind all of that, whether it be GOD or something more ephemeral . . . I deeply believe that his music will be heard and played for as long as there is a human spirit.”

Percussionist Eduardo Leandro takes my sketchbook and furiously writes: “There’s a character in a Milan Kundera novel that is based in gesture. Can’t remember the book’s name. Percussion is the one instrument that cannot be defined by an object, but more by a gesture. Not only hitting an object, but sometimes caressing it or being it, making my own body the object.”

The scope of what one takes in at Yellow Barn over the course of a season is resonant and powerful because of all the possibilities one is given to experience in imagery and imagination. As a visual artist I was moved to questions and inspired to create all this in my own way. Part of a grateful and thoughtful audience, I glimpse the meaning of Emily Dickinson’s poem. I cannot ask to see more than that.

What I see not, I better see—

Through Faith—my Hazel Eye

Has periods of shutting—

But, No lid has Memory—

For frequent, all my sense obscured

I equally behold

As someone held a light unto

The Features so beloved—

And I arise—and in my Dream—

Do Thee distinguished Grace—

Till jealous Daylight interrupt—

And mar thy perfectness—

—Bill Kelly

Watch performances from the Big Barn

Visit Yellow Barn's YouTube Channel to watch performances from the Big Barn, including over 50 from last summer!

Dean Approach (Prelude to a Canon) (2017)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 in B-flat Major,

BWV1051 (1718)

Yeh-Chun Lin, Cara Pogossian, violas; Julia Lichten, Florianne Remme,

Madelyn Kowalski, cellos; Sam Suggs, double bass; Ryan Jung, harpsichord

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) Songs and Proverbs of William Blake, Op.74 (1965)

Nathaniel Sullivan, baritone; Julian Chan, piano

Julian Anderson (b.1967) String Quartet No. 4 (2023)

Yeim Lee, Ele Bienzobas, violins; Jonathan Brown, viola; Gerard Flotats, cello

Who is the other Mozart?

Nannerl Mozart was a child prodigy like her brother Wolfgang Amadeus, but her musical career came to an end when she was 18. A one-woman play puts her back on the stage. In September 2015, on the occasion of the 100th performance of her play The Other Mozart, actress Sylvia Milo writes about her inspiration and process.

"I am writing to you with an erection on my head and I am very much afraid of burning my hair”, wrote Nannerl Mozart to her brother Wolfgang Amadeus. What was being erected was a large hairdo on top of Nannerl’s head, as she prepared to pose for the Mozart family portrait.

It was that hairdo that drew my attention. Nine years ago I was visiting Vienna for the 250th birthday celebrations of Wolfgang Amadeus, and I was thrilled to explore the city following in Wolfi’s footsteps, many of which turned out to be Nannerl’s as well. At the Mozarthaus Vienna – Wolfgang’s apartment – on the exit wall, as if by an afterthought, there was a little copy of the Mozart family portrait. I saw a woman seated at the harpsichord next to Wolfgang, their hands intertwined, playing together. I grew up studying to become a violinist. Neither my music history nor my repertoire included any female composers. With my braided hair I was called “little Mozart” by my violin teacher, but he meant Wolfi. I never heard that Amadeus had a sister. I never heard of Nannerl Mozart until I saw that family portrait.

I was intrigued and determined to find out more. I read Wolfgang Mozart biographies, studied the situation of women and female artists during Mozarts’ time and in different countries, read writings of Enlightenment philosophers, conduct manuals … But the richest source of information came from the Mozart family letters. There are hundreds, and we have them because Nannerl preserved them. Most are written by Leopold and Wolfgang but some of Nannerl’s letters survived as well. Through these letters, sometimes only from the replies to her lost letters, Nannerl slowly emerged. I was able to understand the Mozarts as people, as a family, and through the lens of the times and the social situation in which they lived. I saw Nannerl’s potential, her dreams, her strength, grace and her fight.

Maria Anna (called Marianne and nicknamed Nannerl) was – like her younger brother – a child prodigy. The children toured most of Europe (including an 18-month stay in London in 1764-5) performing together as “wunderkinder”. There are contemporaneous reviews praising Nannerl, and she was even billed first. Until she turned 18. A little girl could perform and tour, but a woman doing so risked her reputation. And so she was left behind in Salzburg, and her father only took Wolfgang on their next journeys around the courts of Europe. Nannerl never toured again.

But the woman I found did not give up. She wrote music and sent at least one composition to Wolfgang and Papa – Wolfgang praised it as “beautiful” and encouraged her to write more. Her father didn’t, as far as we know, say anything about it.

Did she stop? None of her music has survived. Perhaps she never showed it to anybody again, perhaps she destroyed it, maybe we will find it one day, maybe we already did but it’s wrongly attributed to her brother’s hand. Composing or performing music was not encouraged for women of her time. Wolfgang repeatedly wrote that nobody played his keyboard music as well as she could, and Leopold described her as “one of the most skilful players in Europe”, with “perfect insight into harmony and modulations” and that she improvises “so successfully that you would be astounded”.

Like Virginia Woolf’s imagined Shakespeare’s sister, Nannerl was not given the opportunity to thrive. And what she did create was not valued or preserved – most female composers from the past have been forgotten, their music lost or gathering dust in libraries. We will never know what could have been, and this is our loss.

Director Isaac Byrne and I searched for the ghost of Nannerl, and the story she needed to tell in my one-woman play. Period-style movement transports us to the Mozarts’ time using delicate gestures, court bows and curtsies, and the language of fans.

To create the 18th-century world of opulence and of restriction, the set became an enormous dress which spills over the entire stage (designed by Magdalena Dabrowska), with a corset/panniers cage on top. Finally the hair stands as tall as Nannerl’s, after we found the right hairspray to hold it all up-up-up – and yes, it is all my own hair.

Creating music for the show was down to two composers, Nathan Davis and Phyllis Chen, who chose, rather than to try to re-create Nannerl’s compositions, to portray her musical imagination, using the sounds she would have had in her ears: the fluttering of fans, tea cups, music boxes, bells, clavichords.

I’ve been touring The Other Mozart for the last two years: this month marks its 100th performance, how fitting that it will take place just a few steps away from where Nannerl performed in London as a girl.

It has been a long journey to bring Nannerl back to England after an absence of 250 years. I sometimes feel like Leopold Mozart – on a quest to show the world this brilliant Mozart.

"Harriet, Scenes from the Life of Harriet Tubman"

On July 30th Yellow Barn's will present the American Premiere of Hilda Paredes' Harriet, Scenes from the Life of Harriet Tubman at the 2023 Summer Gala, followed by a general performance on July 31st. How did Harriet come to be, and what does it mean to perform it at a chamber music festival?

Hilda Paredes said, "After being invited by Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México to write a new opera, I asked my friend Claron McFadden if she would like to feature in this project and she immediately introduced me to Harriet Tubman. A six-year journey began then, discovering the extraordinary life and personality of Harriet Tubman. I always say and still think that if she had lived in the twentieth century she would have been awarded the Nobel peace prize."

After which Claron offered the following response by Zoom from Barcelona:

Find out more about the performance of Harriet at our Summer Gala on Sunday, July 30

Find out more about the general performance on Monday, July 31

Lei Liang's Six Seasons

Music Haul Flip Side: Baltimore

"Every citizen a storyteller." On this Fourth of July we cannot resist remembering our incredible Flip Side poets. We are proud to share their work with you, alongside Jennifer Curtis, violin, Charles Overton, harp, and Chase Morrin, piano. Thank you to the families of Saint Luke's Youth Center and The Park School of Baltimore. As CJ Williams proclaims at the end of his poem to Langston Hughes and Beethoven: "Baltimore is beautiful!"

Learn more about Yellow Barn Music Haul's Flip Side: Baltimore

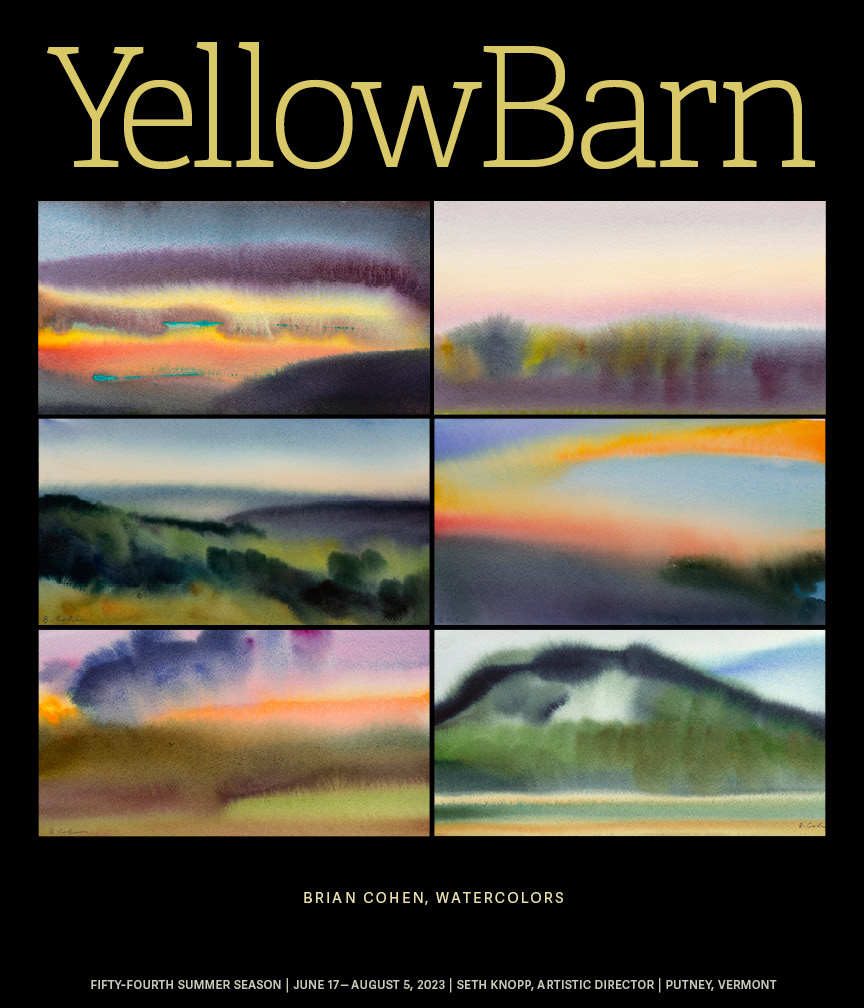

Yellow Barn’s 2023 Summer Artwork

"Shut your eyes, wait, think of nothing. Now, open them ... one sees nothing but a great colored undulation...an irradiation and glory of color. This is what a picture should give us…a colored state of grace." (Paul Cezanne)I had been working in black and white for over twenty years before returning to my earlier infatuation with color. My watercolors are done on site, usually fairly quickly. I apply paint into wet paper, timing the drying of the paper as I lay in new washes of color. Painting in the landscape lets me sit happily observing light, color, and shape, simplifying or obscuring detail in favor of larger forms and the broader swell of color. I aim for a “color chord" or harmony that speaks of time, light, and distance all at once.—Brian Cohen