Yellow Barn Music Haul at the Brattleboro Retreat

Yellow Barn Music Haul at the Brattleboro Retreat

Last summer, Yellow Barn Music Haul visited the Brattleboro Retreat, the first facility for the care of the mentally ill in Vermont, and one of the first ten private psychiatric hospitals in the United States, to bring chamber music to their community. The first performance was geared towards Retreat patients from their Elementary School and Early Education programs, and the second towards all ages. With about 125 children and staff present at both performances, the excitement and connection between musicians and audience was palpable.

During the final week of the festival, Yellow Barn was honored to welcome Retreat employees to the Big Barn for two Retreat Nights, offering them complimentary tickets and thanking them from the stage. Over the course of the two concerts, Retreat employees and their families were able to experience more music from percussionist Sam Um and the Omer Quartet, who had performed at the Retreat.

Konstantin von Krusenstiern, VP of Development and Communications at the Retreat, wrote the following letter of support for the partnership:

Dear Yellow Barn:

On behalf of everyone at the Brattleboro Retreat, thank you for coming to our campus with the Music Haul to perform for our patients and staff. We are also grateful for the complimentary tickets that you provided for folks to attend concerts at your venue in Putney. Approximately 250 individuals at the Brattleboro Retreat benefited from your programming this summer.

All of the concerts were truly fabulous! The children and adolescents in our residential and day programs were totally captivated by the performances. It was also wonderful to see so many of the patients ask lots of questions during the Q&A sessions after the shows. For many of the kids, this was the first time they had ever seen such concerts, and they were totally engaged!

The therapeutic benefit of the concerts was also apparent and without a doubt a wonderful experience for our patients on in their path to recovery. I have enclosed some letters and drawings from some of the children expressing their thanks to Yellow Barn expressing their thanks for the concerts.

The Brattleboro Retreat is exceedingly grateful for our partnership with Yellow Barn and we look forward to collaborating with you again in the future.

Sincerely,

Konstantin von Krusenstiern

Vice President Development and Communications

"Now This is Barnstorming"

On Saturday, May 27, 2017, the New York Times Arts Section featured Yellow Barn Music Haul with a banner headline and a half-page spread during "Music No Boundaries: NYC". Between May 24 and June 1 over 80 Yellow Barn musicians donated performances for 20 concerts across four boroughs of the city.

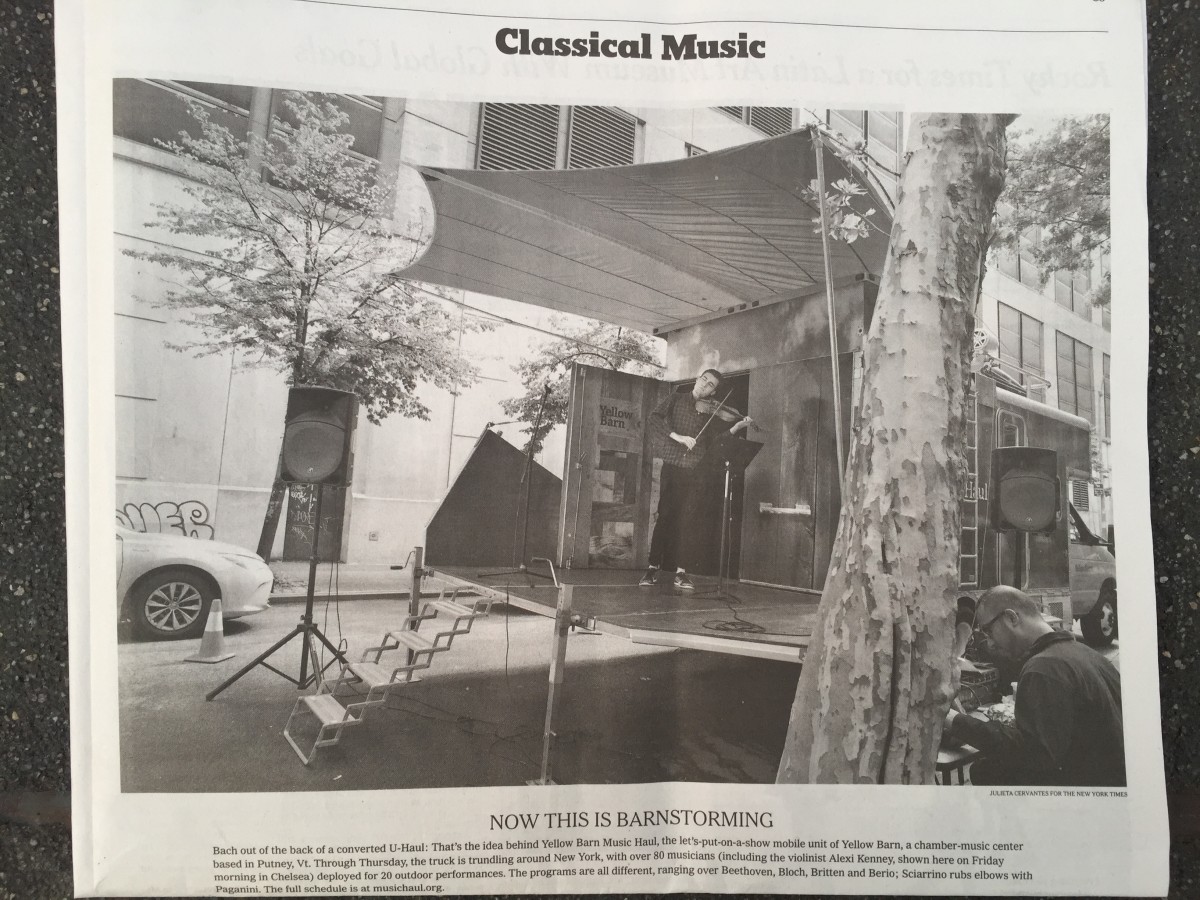

NOW THIS IS BARNSTORMING

Bach out of the back of a converted U-Haul: That's the idea behind Yellow Barn Music Haul, the let's-put-on-a-show mobile unit of Yellow Barn, a chamber-music center based in Putney, Vt. Through Thursday, the truck is trundling around New York, with over 80 musicians (including the violinist Alexi Kenney, shown here on Friday morning in Chelsea) deployed for 20 outdoor performances. The programs are all different, ranging over Beethoven, Bloch, Britten and Berio; Sciarrino rubs elbows with Paganini. The full schedule is at musichaul.org.

"Yellow Barn: Taking it to the Streets"

David Weinenger, who writes a Classical Notes column for the Boston Globe, interviews Yellow Barn's Artistic Director Seth Knopp and Executive Director Catherine Stephan about Music Haul's "Music No Boundaries: NYC" tour for The Log Journal.

Yellow Barn, the famously intrepid summer chamber music festival based in Putney, Vermont, is raising the concept of “taking the show on the road” to a new level. In October 2015 the center introduced Music Haul, a mobile stage in the back of a truck, which allows Yellow Barn’s musicians to perform virtually anywhere the vehicle can travel.

Having already visited Boston, Baltimore, and Dallas, Music Haul now will undertake its most ambitious voyage yet: “Music No Boundaries: NYC,” a nine-day residency featuring performances in four New York City boroughs, starting at noon on May 24. The itinerary includes a long list of neighborhood parks, plazas… even a Bronx street corner that Yellow Barn artistic director Seth Knopp remembers as being particularly vital.

A dizzying array of musicians, including prominent instrumentalists, vocalists, and ensembles, are volunteering their time and services for the tour. This allowed Knopp to program performances that have the depth and experimental richness familiar from the festival’s summer concerts. The tour will include one indoor performance, at National Sawdust on May 28: a program that includes a rare performance of Erwin Schulhoff’s Sonata Erotica for solo female voice.

Knopp and Yellow Barn managing director Catherine Stephan spoke to The Log Journal about the tour, its benefits and potential pitfalls, and what you might get from a chance encounter with music on a New York street.

THE LOG JOURNAL: What made you decide that Yellow Barn needed a traveling stage?

SETH KNOPP: I was actually meeting with a piano technician right next to Carnegie Hall – I was meeting them to look at pianos for the summer [festival]. I got there around 7:30 in the morning, and it was really busy, as it always is in that part of town. The door was open, and the tuner was doing the usual one note, over and over again. And I noticed that, inevitably, people would stop in their tracks and peer in to see what was going on, simply because there was a sound they didn’t expect to be hearing.I thought that was kind of interesting, because we walk by a lot of things in our lives that are a lot more interesting than someone plunking an A over and over again. And I thought, if you could take that moment of interest and curiosity, and then in the next minute have something with artistic intentions, I wonder if you could capture somebody’s attention in a way that it’s without planning, without any kind of anticipation? They would just come upon something, and it would capture their interest.

It was just the germ of an idea. And we were having another conversation about marketing, and we were having a conversation about having an ice cream truck that would go around playing recordings of Yellow Barn music, luring people back to our hall. And then the conversation became more about, this is a big-enough undertaking that it needs to have something to do with our fundamental reason for existence. So live music was introduced. And actually, we got to an idea that feels like a shared idea, because so many people have had the idea of having a traveling stage.

Getting to the reality of Music Haul… that was a little more complicated. [laughs]

(Iaritza Menjivar)

Where’d the idea for this sort of mammoth mobile residency come from?

KNOPP: I think our thought at the beginning was that we wanted to reach a lot of people – to bring music to as many people as possible, and to as many kinds of neighborhoods as possible. The idea of Music Haul is not based on the idea that you expose someone to something, and then they’ll seek out the experience in a “real hall.” We wanted to make this feel like the venue was attractive enough.

In a way, the scope of where we’re going and the kind of repertoire we’re doing was really based on an email I sent out at the very beginning, even before we had an idea of how much we were going to do, to the troupe of YB musicians that have been formed over years and years of the summer festival, and also the residencies that we have during the year.

That was the “this is what we’re doing, are you interested in donating your time and services” email

KNOPP: Exactly. And there was such an overwhelming response – we have 76 musicians participating. I’ll give you one example: [soprano] Lucy Shelton said, “I’m in town that week, I want to do as much of this as possible.” People kind of fell in love with the idea, which was a deeply satisfying thing, and made me so proud to be part of a collection of people that are so much about the communicating of what they do that the contractual element doesn’t even come into play for them. We even have people traveling from other cities to do this. And then the inspiration kicked in: “Look at all the ingredients we have to cook with!” There were just so many different places that we wanted to go.One of our experiences with Music Haul has been that in terms of being exposed to music, that kind of experience is absolutely nondenominational and ethnicity-blind. You could be in one neighborhood that looks one way, and the same number of people stop to listen as you’d have in another neighborhood. It simply doesn’t matter what the demographics are. It’s as if there is something at the DNA level in every human being that actually overrides anything more superficial. And that’s a very moving thing to see happen.

You could be in one neighborhood that looks one way, and the same number of people stop to listen as you’d have in another neighborhood. It simply doesn’t matter what the demographics are. It’s as if there is something at the DNA level in every human being that actually overrides anything more superficial.

Give me a glimpse into the programming process. How did you match up repertoire with locations?

KNOPP: There were partnerships that were formed from every-which direction. Some of them came from a certain location: Symphony Space, Carnegie Hall. Some of them from the fact that we wanted to have a certain program at a place that seemed appropriate. There’s a children’s museum of art and storytelling that we wanted to have because it would be the perfect place for that program. So then we had to go and look at the location and see if it was physically possible for Music Haul to come and unfold the stage, and comfortable for people to come and listen.This was a very different programming experience for me. I think Catherine wore out a pair of shoes going to places, and knows New York better than some New Yorkers. We’re in Brooklyn for eight hours on the 27th for Smorgasbord Saturdays – that was a place I think a couple of our musicians had suggested. So we had input from a lot of different places.

(Iaritza Menjivar)

What kind of hazards are there to planning and executing an undertaking like this, to make it fulfilling for both players and listeners?

KNOPP: In terms of the pitfalls, the practicality, we feel that we [directors] need to stay at a distance from Music Haul. Especially when it’s not live musicians, we’re just playing off the speakers, there’s this thought that people on the street are used to being stopped, people trying to sell them something… If we distance ourselves from the truck, so people have no idea that it belongs to us, they are much more likely to stop and listen and have their own experience.The same thing is true with live musicians. We feel like this truck, in a way, takes the presenter out of the middle, and allows the musicians who are playing to have direct relationships with the audience. And it’s also because the audience can leave at any point – it’s completely up to them. They can be self-selecting, which means it’s truly their experience. They decide to stay because of what they hear, not because of what they expect to hear. And people who wouldn’t ordinarily stop for this because they might be fearful of going someplace they’ve never gone before, or not understanding the protocol, or even know when it begins or ends – that whole fear is taken away.

Then there are all the physical things we have to deal with when we’re scoping out things, which Catherine knows a lot about…

CATHERINE STEPHAN: For a while when we were scouting, I was literally always looking at the ground: Are there potholes here? Is there a bench that’s going to mean we can’t open the door? I kept forgetting to look up for trees, which would interfere with the canopy. [Laughs] The mental checklist when you’re driving around and looking for possibilities has definitely grown over time.

The truck has a full-stage version and a half-stage version, which allows us to tuck into a curb lane. So, for example, a lot of our New York City street permits are just to be in the curb lane somewhere. And then we can do the full-stage version in plazas and parks and playgrounds.

One thing that really stands out in the programming is the chance to hear Tony Arnold sing Schulhoff’s Sonata Erotica at National Sawdust.

KNOPP: You’ve hit on the one indoor performance that we’re doing. We wanted to do one indoor performance, because we wanted people to understand the fundamental essence of Yellow Barn. That’s a program that we did, I think, two years ago, with a little bit of tweaking.Personally, I’ll tell you that that piece – from a programming aspect, this tour aside – has been something that I’ve been thinking about for a very long time. On the surface of it, that piece was meant by Schulhoff to be a cabaret piece – on the front of the score he writes, “For Men Only.” It’s a difficult piece to program, not for reasons that the audience would be somehow scandalized or uncomfortable, but more, how do you place it in the program, other than having it be a sort of talent-show program with one thing after the next? You put it in there for the thrill of it. And I’d always wanted to find a way of doing it that had another meaning.

So it’s set in this way that I hope makes it more about what we’ve lost when we lose the people that we lose in these tragedies. It’s with Reich and Wagner, and it’s meant to have kind of a different impact.

What would you want a listener to take away from the experience of a Music Haul performance, whether they stop and listen for five minutes or two hours?

KNOPP: Music is invisible, and it can bring something beautiful to an inner city neighborhood, it can bring a soul to a downtown financial district. It can bring us to what most makes us human – all in a moment, all in a flash of sound. And I kind of feel that to hear music in that way can remind us that what we can see and touch and name is just a very small part of our world. It has power in that moment to rebuild us, inside and out.I think it’s a wonderful thing to witness how music, in a way, needs no explaining. And hopefully, what they’ll come away with is just having had an experience that somehow deepens them, or it changes their day, their moment, and it puts them in touch with something that wasn’t there a moment ago. It’s a pretty simple thing, but for me it’s an important one.

The Yellow Barn Music Haul visits New York City May 24-June 1; see www.musichaul.org for complete, up-to-the-minute listings and advisories.

Music No Boundaries: NYC 2017

Photos by Ben Bocko

MUSIC NO BOUNDARIES: NYC

May 24-June 1, 2017

After touring Boston, Baltimore, and Dallas, Yellow Barn brought Music Haul to New York City for 9 days of sidewalk, plaza, and neighborhood performances in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. Over 80 Yellow Barn musicians performed in 20 locations, from Times Square and Carnegie Hall, to PS21 and Bathgate Community Garden.

Titled “Music No Boundaries: New York City”, Seth Knopp’s programming included a day dedicated to Bach’s cello suites and a Memorial Day performance of “Musicians Indivisible: Protest Mix Tape” with Broadway musicians; the Juilliard and Brentano String Quartets performing late Beethoven, Bartók, and Mozart; the JACK Quartet and Sandbox Percussion; spoken word performances and Carnegie Hall’s Ensemble Connect; and even a new work inspired by Dick van Dyke’s one-man-band.

Locations and Partners

For complete tour and program information, go to www.musichaul.org/tour/NYC2017.

PS21 + JS185, Queens

Bathgate Community Garden, Bronx

W. Gun Hill Road at Jerome Ave., Bronx

Wagner Park, Battery Park City, Manhattan

The Relief Bus/Chelsea Park, Manhattan

Carnegie Hall and Ensemble Connect, Manhattan

Plaza de Las Americas market at United Palace, Manhattan

Smorgasburg Saturday, East River State Park, Brooklyn

Myrtle-Wycoff Plaza, Queens

Union Square Plaza, Manhattan

Morandi restaurant at Waverly Place, Manhattan

Times Square, Manhattan

Heavenly Rest Stop Café, 5th Ave. at 90th St., Manhattan

Broadway Ave. at 108th St., Manhattan

Richard Tucker Square across from Alice Tully Hall, Manhattan

Boulevard Family Residence, Queens

Rosarito Fish Shack, Wythe Ave. at 7th St., Brooklyn

Sugar Hill Children's Museum for Art and Storytelling, Mannhattan

Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, Manhattan

Union Square Park, Manhattan

MUSICIANS AND ENSEMBLES

Jonny Allen percussion

Eric Allen cello

Misha Amory viola

Daniel Anastasio piano

Garrett Arney percussion

Oliver Barrett trombone

Hamilton Berry cello

Grant Braddock drums

Brentano String Quartet

Natasha Brofsky cello

Nate Brown guitar

Julia Bruskin cello

Lizzie Burns double bass

Victor Caccese percussion

Jay Campbell cello

Serena Canin violin

Andrea Casarrubios cello

Sarah Elizabeth Charles voice

Andy Clausen trombone

Ronald Copes violin

Romie de Guise-Langlois clarinet

Jah’china De Leon spoken word

Lee Dionne piano

Erika Dohi piano

Pete Donovan double bass

Margaret Dyer viola

Ensemble Connect

Madeline Fayette cello

Magdalena Filipczak violin

Nykeira Franks spoken word

Rosie Gallagher flute

Goliath Duo

Andrew Gonzalez viola

Melanie Henley Heyn soprano

Zubin Hensler trumpet

Brandon Ilaw percussion

Ari Isaacman-Beck violin

JACK Quartet

Qing Jiang piano

Juilliard String Quartet

Gilbert Kalish piano

Michael Katz cello

Bixby Kennedy clarinet

Alexi Kenney violin

Ariana Kim violin

Yoonah Kim clarinet

Seth Knopp piano

Willem de Kochon trombone

David Krakauer clarinet

Gwen Krosnick cello

Nicolee Kuester French horn/spoken word

Christine Lamprea cello

Mari Lee violin

Nina Lee cello

Joseph Lin violin

Jennifer Liu violin

Jazimina MacNeil voice

Curtis Macomber violin

Sunshine Martin spoken word

Thomas Mesa cello

Chase Morrin piano

Riley Mulherkar trumpet

Musicians Indivisible

Adelya Nartadjieva violin

Brian Olson trumpet

Christopher Otto violin

Edvard Pogossian cello

John Pickford Richards viola

Ian Rosenbaum percussion

Sandbox Percussion

Nathan Schram viola

Astrid Schween cello

Lucy Shelton voice

Speed Bump

Mark Steinberg violin

Samuel Suggs double bass

Terry Sweeney percussion

Kathleen Tagg piano

Rémy Taghavi bassoon

Max Tan violin

Cordelia Tapping violin

Roger Tapping viola

Suliman Tekalli violin

Christopher Theofanidis composer

Jason Treuting percussion

Sam Seyong Um percussion

The Westerlies

Aaron Wolff cello

Austin Wulliman violin

Julia Yang cello

Sound Engineer: Dev Ray

Stage Manager: Michael Bradley Cohen

Assistant Stage Manager: Eric Clem

Final Thoughts

Pianist Marisa Gupta offers final thoughts on her two artist residencies at Yellow Barn, both titled Faithful to the Spirit, which focused on the influence of recordings on the interpretation of chamber music:

I would like to preface this post by offering my sincerest thanks to Nick Morgan, whose research into the National Gramophonic Society was the inspiration for our residencies. The NGS made the first complete recordings of important pieces of chamber music (including major works by Debussy, Schubert, Brahms, Elgar, Vaughan-Williams, Ravel, and others), often in consultation with the composers. Though largely forgotten today, it is an invaluable resource for all performers.

Interpretation au deuxième degré

The French distinguish between interpreting something au premier ou au deuxième degré (in the first or second degree). A joke, concept or message taken at the ‘first degree’ means it is viewed literally, overly seriously, or at face value. There is no exact English equivalent for au deuxième degré but it means roughly to interpret something with an understanding of hidden meanings.

Our residencies at Yellow Barn have been about exploring musical possibilities at the second degree. Early recordings hint at the possible hidden meanings behind the signs and symbols of notation. While most musicians are aware of certain limits of notation, comparing historical recordings with modern ones illustrate that the ambiguities are greater than interpretations today suggest. Listening to performances through the history of recording, one hears a radical shift in how a composer’s score is viewed philosophically: a shift from the second degree (a plethora of un-notated expressive devices and tendency to freely adapt the score) to the first degree (the widespread approach of today which subscribes to strict and literal fidelity to the written notation).

Why this shift (which became particularly pronounced after WW2) occurred is complex. Migration contributed to the disappearance of national schools, leading to greater uniformity of interpretations. In earlier eras, there was less distinction between composers and performers, and professional and amateur musicians. Before recordings, if people wanted to hear a performance, they had to hear it live or play it themselves. Most performers were composers too, and their playing and composition styles were intimately related. To be a virtuoso meant not just technical prowess at the instrument, but also at improvisation.

Today musical life is more compartmentalized and specialized. Most composers and performers eventually follow distinct educational and career paths. Virtuoso performers today are not generally skilled improvisers, though technical accomplishment across the board is astonishing. Technology is ubiquitous; listeners can hear pieces performed to the highest standard of perfection, recorded under the most auspicious of conditions at the press of a button. We have shifted from viewing interpretation as free re-creation (improvisations, and even approximations of a piece), to a view in which we are expected to be faithful executants – adhering to the letter of a composer’s score. Furthermore, the rise to prominence of the conservatory system, competitions and the field of record reviews meant the need for an objective measure of quality; one of the benchmarks has become fidelity to the score.

To our modern sensibilities, liberties taken in earlier eras may seem like distortions of a composer’s intentions. It is possible we have reached a height of folly of another sort – one that mistakenly equates strict and literal fidelity to the score with being faithful to the spirit of a composer’s intentions.

These residencies have made us realize that the nature and degree of compliance we should adopt in interpreting music is more nuanced than we have been conditioned to believe. As the defining characteristic of performances on early recordings is the individuality and diversity of playing styles, this exploration has surprisingly made me less concerned about performance practice. Instead, what our residencies at Yellow Barn has allowed us to do is consider and re-evaluate one of the most powerful influences on musical life (recordings) over the last century. It has fired our imaginations, allowing us to consider a wider array of hidden meanings behind the music we perform. Most importantly, it has inspired us to remain faithful to both the time in which we live, and our voices as individuals.

Reflections

Later this month, pianist Marisa Gupta, violinist Maria Włoszczowska, violist Rosalind Ventris, and cellist Jonathan Dormand will return to Yellow Barn for a second residency exploring playing styles heard on early recordings. The quartet will culminate their residency, entitled Faithful to the Spirit, with a concert on Monday, March 6 at 8:00pm at Next Stage in Putney.

In this post, Marisa reflects on last year’s residency and introduces the topics she hopes to explore this year.

Reflections

There was controversy recently when Nigel Kennedy accused the music establishment of producing “factory lines” of pianists and violinists, emphasizing technical perfection at the expense of individuality. “You do hear some amazing talent, but [it] has been kind of fettered,” he told the Observer. “If you listen to one version of a Brahms concerto or Beethoven against another one, they’re unfortunately too similar.” It has been interesting to contemplate this as I prepare for our return to Yellow Barn and reflect upon our residency last season.

Though I think it is doubtful that music colleges and record companies have consciously colluded to produce perfect automatons, devoid of individual expression, Nigel Kennedy raises an important point that lies at the heart of our residency: the need to question the uniformity and rigidity of playing styles today.

Our residency at Yellow Barn has allowed us to examine some of the complex factors that unwittingly led to this conformity (see earlier blog posts for more). The sense of discovery, risk taking and creativity associated with Yellow Barn has made it a fruitful environment in which to experiment with more daring ways of playing - ever supported by Seth Knopp’s encouragement to expand these boundaries further and further.

Our time last season was transformative in ways we didn’t expect. The lightness, brisk tempi, and ‘swing’ of Grieg’s own playing compelled us to propel our performance of his Cello Sonata forward, beyond our natural inclinations.

Performing Three Pieces for Piano Trio, based on fragments by Elgar though not completed by him, was liberating because it was music we neither previously knew, nor viewed as hallowed (as the pieces were not completed by the composer). Thus, we were more adventurous in experimenting with different ways of capturing the spirit of Elgar’s music, particularly in regards to tempo fluctuations, rubato, and synchronicity - inspired by some of the early performers we heard. This led to extremes in performance that we perhaps wouldn’t have attempted in a more canonical work.

The Piano Quintet in c minor by Vaughan Williams was a revelation for us. It was performed during the composer’s life, but a ban was placed on its publication, as Vaughan Williams did not consider it a mature work. Luckily for us his wife lifted the ban after the composer’s death and the piece is now published. In it one finds a great and moving masterwork. Though it was not a piece we were overly familiar with, in the process of rehearsing, one of the questions posed by Rosie Ventris was, were our interpretative decisions truly ours, or did we play passages in a certain way because that was what we heard in the few modern recordings that did exist of the piece? It made me question more broadly - to what extent is my playing genuinely mine? Am I truly conscious of the degree to which I am influenced by recordings I hear?

In trying to work with a wider expressive palate, some things were effective, and others, not quite idiomatic (yet) within the expressive world we have been conditioned in. Some fingerings from the original performers simply did not work with our physicality, nor did they sound good to our ears. There were instances where the string players experimented with slides, and while they may have been historically correct our attempts at that stage sounded contrived.

Ultimately though, our goal was never to resurrect a dead style. Rather, our time at Yellow Barn has been about looking to the past to help us unlock richer ways of communicating the spirit of the music we perform, in a way that is modern, energetic and emotionally direct. We look forward to seeing where the second part of our residency leads us.

(Photo taken after last year's Faithful to the Spirit residency concert)