Faithful to the Letter or the Spirit?

Yellow Barn is thrilled to welcome pianist Marisa Gupta for a week-long residency exploring the ways in which recordings have shaped playing styles and the culture of performance. This Yellow Barn Artist Residency, entitled Faithful to the Spirit, continues Marisa’s study of recordings held in the British National Sound Archives. Her project is made possible by a British Library Edison Fellowship and a grant from the Vaughan Williams Charitable Trust. Alongside violinists Philippe Graffin and Maria Włoszczowska, violist Rosalind Ventris, cellist Jonathan Dormand, and double bassist Lizzie Burns, Marisa will culminate her residency with a concert at Next Stage in Putney on Sunday, May 1 at 3pm.

We invite you to read Marisa’s initial thoughts on her project, post your own comments, and look for future postings from Marisa as her residency progresses.

Having learned Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 109 during my studies at the Royal Academy of Music, I played the piece at the time for a fellow student. Upon finishing, she marveled at my meticulous adherence to Beethoven’s detailed and sometimes perplexing indications. ‘You observe every indication in the score!’ she exclaimed. I feigned modesty but was, in fact, self-satisfied, having put the music first; above all capturing, as best as I could, Beethoven’s desires, passed down to us through his hallowed score. In hindsight I look back on the incident with amusement and slight chagrin at my deferential naivety and complacence, having misconstrued a faithful reading of the score for artistry and a historical respect for Beethoven’s music.

Over the past few years, I have been immersed in the music of a composer much less revered than Beethoven, but whose understated music has, nevertheless, enchanted some of the greatest artists of our day: the Catalan composer Frederic Mompou. Whilst studying and performing over 2 hours of previously unpublished music by the composer, I came across rare recordings of Mompou playing his own music (dating from 1929 to 1974). In doing so, I accidently stumbled into the world of early recordings, changes in playing styles during the age of recording and the debates surrounding the topic. To what degree this has impacted my own performances is difficult to measure. But, it has profoundly changed how I think about music. I have come to a better understanding, not necessarily of historical performing styles of the era, but of something of greater importance: how we interact with music today, and some of the conditions responsible for our modern perspective.

I have decided to expand this exploration into the realm of chamber music (in conjunction with the British Library and Yellow Barn). The starting point for this project is a little known enterprise called the National Gramophonic Society, created not long after Gramophone magazine in 1924 by the publication’s founder Compton Mackenzie. The NGS made the first complete recordings of important pieces of chamber music (including major works by Debussy, Schubert, Brahms, Elgar, Vaughan-Williams, Ravel, and others), often in consultation with the composers. It folded in the 1930s and has been largely forgotten, though its sister publication Gramophone still thrives. The NGS gives us a glimpse of musical life before the influence of recordings took hold, and its little known performances tell us something about the spirit of music making that words and notated scores cannot.

In writing Miroirs, Ravel was inspired by a quote from Julius Caesar: ‘the eye sees not itself/But by reflection, by some other things’. This encapsulates the raison d’être of this project. Through ‘some other things’ (in this case early recordings, the surrounding musical culture and philosophical debates) can we make sense of our current culture of music making.

By transforming the ephemeral into a lasting object, the evolution of recordings has contributed to a strict musical orthodoxy, though we are hardly aware of it. If we can re-discover what used to be (and by proxy, understand what is now) we can possibly breathe new life into music making and the experience of listening to classical music today. It is helpful to understand some of the transformations that occurred because of recordings. Some shifts were already in the process of taking place, but it is likely that recordings accelerated the pace of these transformations towards extremes that define much of mainstream classical music making and listening today.

Before recordings, concerts were rowdy, exuberant, riotous affairs. This contrasts with today’s mostly somber presentations of predictable pieces, performed in their entirety, and experienced in reverential silence.

There has also been a shift in attitudes towards performance. Prior to recordings, performances could be improvisations, adaptations – even approximations of composers’ written works. This has evolved to what the music journalist Alex Ross labels the ‘cult of precision’: clean, literal and an often un-historical respect for the score that characterizes performances today.

Many of these shifts and their philosophical underpinnings have been well documented and much debated by scholars and other commentators. In spite of this, these debates have had little impact on the world of mainstream professional performance and audiences. So whilst this project encompasses a number of complex topics, beyond the scope of a humble blog, I (along with the other musicians taking part and guests) will endeavor to bring the dialogue out of the scholarly world into the awareness of mainstream performers and listeners. We will also share live performances from Yellow Barn. The hope is to instigate a re-thinking of certain aspects of music making that have become too rigid for performers and audiences alike, and that are far from what earlier composers and audiences would have expected.

—Marisa Gupta

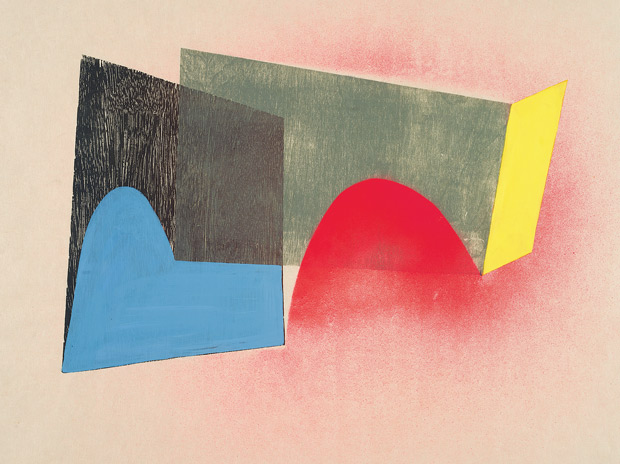

Yellow Barn’s 2016 Summer Artwork

Rachel Gross, Arches, 2014, 16.5 x 20.5”, woodblock relief, spraypaint stencil, and acrylic on Kitakata paper

Courtesy the artist

I think of my prints as spaces to enter with the suggestion of landscape and essential architectural forms. In this image, Arches, the different qualities of texture, color, and shape represent different places in time. As they line up they harmonize in way that allows us to see them all at once.

—Rachel Gross

Rachel Gross (b.1970) makes prints that combine etching, woodblock relief, and paint. In her work she creates an illusion of space that alternates between depth and flatness through the layering of rectilinear forms that recede in space. Gross also makes shaped panels that were inspired by the plywood shapes she cuts out for her relief prints.

Rachel Gross received her MFA in printmaking from Tyler School of Art, in Philadelphia, PA. She is an Artist Member and on the Board of Directors at Two Rivers Printmaking Studio in White River Junction. She has had solo shows at The Aidron Duckworth Museum, Hooloon Gallery in Philadelphia, Norwich University, Plymouth State University, and AVA Gallery in Lebanon, NH. Her prints are in several major public collections including the Boston Public Library, The Southern Graphics Council Print Collection, the Hood Museum, and the Mead Art Museum. Gross has been an Artist Resident at Yaddo and at Northern Print in Newcastle, UK. She has taught printmaking and foundations at the Savannah College of Art and Design, The Center for Cartoon Studies, and Amherst College.

You can see more of her work at rachelgrossprints.wordpress.com.

Music No Boundaries: Putney, Baltimore, and Dallas

Yellow Barn Music Haul Inaugural Tour

Yellow Barn Music Haul’s inaugural road trip was a cross-country journey that began in Putney VT, continued on to Baltimore MD, and concluded in Dallas TX. The Music Haul visited ten locations over the course of seven days, ranging from schools to neighborhood gathering places. The final performace took place on October 22, 2016 at the Nasher Sculpture Center, which celebrated the opening of its Soundings concert series with Music Haul.

“Yellow Barn Music Haul takes music out into the community, out into the streets, where people can encounter it in ways that are as meaningful as they are unexpected. This is something we feel is absolute with Nasher’s mission, with our purpose, and something that will be really embraced in Dallas,” says Nasher Sculpture Center Director Jeremy Strick. “I think that the partnership between Soundings and Yellow Barn has had a profound impact on Dallas. People really look forward to the performances and simply to the presence of the musicians from Yellow Barn. These are occasions for excitement and for joy.”

Find out about Yellow Barn Music Haul

Read more about the inaugural tour

View the concert program from Soundings: New Music at the Nasher

Making the Experimental Accessible

(Photo courtesy Nasher Sculpture Center)

Catherine Womak writes about Yellow Barn Music Haul for D Magazine:

When planning an outdoor concert, perhaps it’s not a great idea to center the program around not just one, but two pieces of music titled “It’s Gonna Rain” (by Steve Reich and the Sensational Nightingales respectively). On Thursday evening, as if taunted by the music itself, the Texas skies opened up and a massive rainstorm forced the Nasher’s planned outdoor Soundings concert indoors. Call it prophetic or serendipitous, but the end result was a mesmerizing display of reverberating sounds, an alternative musical experience that was just as fascinating (if not more so) than the one planned.

The consistently evocative and interesting concert series Soundings: New Music at the Nasher opened its sixth season Thursday night with a concert that was supposed to feature Yellow Barn’s Music Haul, an alternative, flexible outdoor concert “hall” that can transform any street corner into a performance venue.

Yellow Barn’s Music Haul is actually a used 17-foot U-Haul truck that has been retrofitted by a team of designers into a sort of traveling pop-up concert hall (think: the classical music equivalent of a food truck). Along with a talented troupe of musicians, the transformed U-Haul truck is wrapping up its inaugural tour this week in Dallas, where it was supposed to have been set up on Flora Street Thursday night for an outdoor Arts District performance (the group did perform outdoors Wednesday night in the Bishop Arts District under friendlier, dryer skies).

The music presented on this tour is typical of what you might expect from the Nasher’s Soundings series. Avant-garde and modern, this is music that some might view as inaccessible, the kind of art music that appeals to jazz geeks, contemporary-art-gallery-goers and music school nerds who never miss an episode of Meet the Composer. The Music Haul concept is interesting because it seeks to make this somewhat esoteric music accessible to a more diverse audience by performing, quite literally, for your average man or woman on the street. While I didn’t get to see it in action outdoors, I’d imagine the schtick works. Who wouldn’t stop, if even for a few minutes, to watch a mesmerizing accordion/violin duet, see an intricate piece of music played entirely on beer and liquor bottles, or watch as a musician performs hand gestures meticulously synchronized to recorded sounds?

On Thursday evening, the Music Haul truck was backed up to the Nasher’s front doors, but the music itself was moved out of the rain and into the museum’s main entry hall. To maintain the feel of a flexible outdoor concert, audience members were handed folding stools as they entered and instructed to position themselves wherever they wanted in the space. The eclectic program opened with music composed and performed by the fantastic concert accordionist Merima Ključo. In her hands, the accordion was transformed, blending beautifully with amplified violin and voice and expanding preconceived notions about the capabilities and qualities of the instrument.

Klujco was joined throughout the evening by percussionist Ian Rosenbaum, sound engineer Julian McBrowne and members of the band Rabbit Rabbit (Carla Kihlstedt and Matthias Bossi). Together they presented a mesmerizing and eccentric collection of pieces by living contemporary composers. The most recognizable name on the program was that of Steve Reich, whose It’s Gonna Rain, Part I (1965) and Music for Pieces of Wood (1973) were given memorable performances. Repetitive pulsations that would have dissipated in the open air reverberated deafeningly in the museum’s clean, empty space. The sound was intense and completely engrossing, making the music of the gospel quartet that followed it all the more refreshing.

Mark Applebaum’s Aphasia (2010), performed by Ian Rosenbaum, was one highlight of the night. The piece is as much performance art as it is music, and Rosenbaum’s stage presence was completely engrossing as he gestured in perfect synchronization to pre-recorded sounds. Rosenbaum also captured the audience’s attention with a focused, thoughtful performance of Christopher Cerrone’s Memory Palace, in which he played a prostrate, amplified guitar like a harp and transformed a collection of bottles into a complex instrument.

This was a fascinating and engaging evening of music that thoughtfully intertwined the familiar and the avant-garde. Indoors it was a more intense experience than it likely would have been on Flora Street. But if the goal of this project is to make experimental music more accessible, it will likely succeed wherever it lands, because engrossing performers like Rosenbaum, Kljuco and Rabbit Rabbit will capture audiences’ attention no matter how strange the sounds they make.

The Music Hall Exits the Building

(Photo: Zachary Stephens, courtesy Nasher Sculpture Center)

Jeremy Hallock writes for the Dallas Observer:

In The Shawshank Redemption, Tim Robbins plays Mozart over the prison’s public address system and locks himself in the control room. All the prisoners stop what they are doing and listen. They were shocked that it was actually happening, but inspired. And they understood the music. When Seth Knopp brought musicians to play chamber music on a street in a particularly brutal part of Baltimore, it seemed to surprise and inspire people in a similar way.

It was one of the most impoverished neighborhoods in West Baltimore. Many of the houses were boarded up with the words “Thou Shalt Not Kill” written on them. In those neighborhoods, the only beauty is typically what people create for themselves. But the music of Bach mesmerized the neighborhood's residents, who stood around and took pictures.

Creative director Seth Knopp kicks off the sixth season of The Nasher’s Soundings series by combining it with Yellow Barn’s Music Haul, a project that puts music halls on streets. Before the performance Thursday night on Flora Street in front of the Nasher, there will be a daytime community performance today and perhaps tomorrow: Follow the Nasher on social media to find out where.

Knopp is artistic director of Yellow Barn, an international center for chamber music out of Southeastern Vermont. Yellow Barn’s Music Haul is a traveling concert stage. “It’s the feeling of a concert,” Knopp says. “People don’t have to go through the formality of attending something, something comes to them.” He understands that chamber music excites the senses, creating natural curiosity. Knopp believes this will help people realize that it’s not important to “understand” the music.

In addition to giving impromptu performances in neighborhoods, Yellow Barn’s Music Haul also performs at schools and has more formal events, like the performance Thursday night in front of the Nasher. Each program is different, curated specifically for its site. “We’ve done six concerts incredibly varied in nature,” says Knopp. “Each one has been an incredible learning experience.” Whether listeners knew the composer or not, they seemed transfixed by what they heard, he says.

Knopp knows there are many people who have never been to a classical music concert. “They think they aren’t interested in what they label as classical music,” he says. Some may think they don’t know enough about classical music to attend a concert, but Knopp insists this just isn’t the case. “The only people who need to be educated in the equation are the musicians who are performing,” he says. “It’s their job to make it communicate to anybody. Beethoven didn’t write his music for conservatory graduates and professors, he wrote it for humanity. Bach wrote his sacred music for people in church.”

Yellow Barn’s Music Haul will perform tonight in Bishop Arts. The exact location has not yet been disclosed, but the Nasher will announce it through social media. The program has not yet been finalized, but programs will be handed out during the performance. There may also be another street performance tomorrow during the day.

“This sort of thing has never been done before,” says Knopp. “The idea of rock concerts on these stages has been done.” But the Yellow Barn’s Music Haul doesn’t perform on a flatbed truck; it unfolds into something that really does resemble a music hall on wheels. It tries to create a beautiful setting, the feeling of being in another space, like walking into a music hall. The music begins as the stage is being set up, so there is no anticipation. The performance just starts unfolding.

Knopp came up with the idea when he was across from Carnegie Hall at a piano store one morning. There was rush hour traffic and a piano tuner was banging on a piano. “It’s not the greatest sound in the world,” Knopp says. But throngs of people walking by were curious about the noise. It was something out of context, enough to make them stop and peek into the store. During rush hour traffic on a busy street, it surprised Knopp that a single note being played on a piano could cause so much curiosity.

Somewhat surprisingly, Knopp actually enjoys giving up the cozy setting of a normal music hall. He likes transitioning from programming for a concert stage to a street, realizing an increased need for amplification. If church bells are going to ring during a performance, he has to find a way to make it work with the program. There are contingencies that cannot be planned for, but only a hailstorm has stopped a performance so far. At one performance, the music was echoing off the backs of buildings. “We got this kind of amazing stereophonic delay system,” says Knopp.

Yellow Barn’s Music Haul performances are some of the most moving experiences he’s had. “Conversations happen all the time about elitism,” Knopp says. “About how the arts are for a privileged few.” But as a child, he wanted to make music solely because it spoke to him. And he knows it can speak to anybody.