A New Yellow Barn Position

Yellow Barn creates new Managing Director position, appoints Maria Basescu

On the eve of its 50th Anniversary season, Yellow Barn has filled a new senior-level staff position. This coming September, Maria Basescu will assume the role of Managing Director, joining Executive Director Catherine Stephan and Artistic Director Seth Knopp in positioning Yellow Barn for its next 50 years.

As a creative partner, Ms. Basescu will have an essential position at one of the most highly regarded chamber music centers in the world. Seth Knopp, appointed by founders David and Janet Wells in 1997, said, “For many years Yellow Barn has had the pleasure to work with Maria at Next Stage, Putney’s treasured performance venue. Her deeply emotional connection to the arts, her belief that lives can be changed when we communicate through them, and her unique ability to turn that connection and belief into a meaningful reality, will have a profound impact on the work we do at Yellow Barn.”

Ms. Basescu completes a staff restructuring for this venerable arts institution based in southeastern Vermont, with a national agenda and a growing international presence. “Maria is the ideal person for this new position,” said Catherine Stephan. “She brings significant insight and understanding to Yellow Barn, together with an innate ability to manage the scope and geographic breadth of our year-round programs.” In addition to an array of responsibilities that are critical to the daily operation of Yellow Barn’s programs (its 50-year-old summer festival; the Young Artists Program in June; the first Artist Residencies program in the United States for performing musicians; and national tours with its one-of-a-kind traveling stage, Yellow Barn Music Haul), Ms. Basescu will contribute directly to the implementation of Yellow Barn’s strategic plan, including taking Yellow Barn Music Haul to scale and establishing an artists’ residence and center for music and social dialogue.

Maria Basescu has been the founding Executive Director for Next Stage Arts Project since 2013. Jim Johnson, Chair of the NSAP Board of Directors, said, "Maria’s work at Next Stage has been instrumental in positioning the organization for the next phase of growth. She was our first Executive Director, and guided us through the modernization of 15 Kimball Hill and helped dramatically expand the reach of Next Stage programming. We wish Maria well in her new role, and look forward to our continued collaborations with Yellow Barn."

Ms. Basescu’s deep experience in arts administration includes serving as President of Annapurna Concerts, Public Relations Director for Emerson College’s Division of Performing Arts and Associate Director of Media and Public Relations for the Boston Mayor’s Office of Business and Cultural Development. She has also served as a senior executive in communications and external affairs for Northern Berkshire Healthcare, the Brattleboro Retreat and Marlboro College, and as Senior Advisor with the strategic communications firm Denterlein.

Ms. Basescu has a B.A. in Sociology from Dartmouth College, is a graduate of the Snelling Center for Government’s Vermont Leadership Institute and a member of the Association of Performing Arts Professionals.

Said Basescu, “I am thrilled and honored to be joining the outstanding Yellow Barn team. I look forward to supporting the creative passion, excellence and growing international reputation of this exceptional organization.”

Young Artists Program musician interviews

This week we sat down and talked with two of our YAP musicians, Dawn Kim and Lydia Rhea.

Dawn, 19, is a violinist studying at The Juilliard School. In her interview, Dawn shares her approach to chamber music.

While playing chamber music, it’s really important not only to listen to yourself while playing, but listen to your chamber group members. And also being open to everyone’s suggestions.

Score studying is very important and also listening to various recordings to get an idea of the piece. Not necessarily to use their ideas but to get a sense of how the piece is supposed to go.

Sightreading music with friends can be a really fun way to learn more rep and just have a good time.

And lastly, the biggest thing about being in a chamber group is trusting each other and going on this amazing journey and trusting that at the end of it all we will all be better musicians.

Lydia, 19, is a cellist studying at the Cleveland Institute of Music. In her interview, Lydia shares her preparation process before a performance.

My mental preparation for a performance starts a few weeks before the actual performance. I’d say about two or three weeks beforehand, I start doing run-throughs of a piece. I don’t let myself stop because that’s when I take mental notes of any pitfalls I might have, of any memory slips that might be happening. I find that when you are doing mock run-throughs of your pieces for an audience, it puts you in a much different mental state than you would be in when you’re doing it in your own practice room.

After you’ve mentally prepared yourself for everything– if I have never been in the space before that I’m going to be performing, I often Google Image [search] the stage and the hall so I can mentally set myself up for knowing what the stage is going to look like. I practice walking into a room. You have to practice sitting outside a room for ten minutes beforehand and walking in because I think that waiting period is something we don’t practice a lot, but it’s something that happens at every single performance that you will ever do. You don’t get to play a shift thirty times and then go on stage and do it. You have to sit there and make sure it’s an internalized within yourself beforehand.

The day of a performance, I am super picky about everything that I have in my bag. I have my rosin, I have my rock stop, a stand if I need it, my iPad, back up music– everything like that. I triple check everything. On the way to the performance, I’m totally one of those people that plays through the piece in my head, doing any spots that I might have run-throughs with. That, for me, creates a road map in my head and it makes me feel much more secure once I get on stage.

When I’m back stage, I definitely take deep breaths, especially if it’s a solo performance and I’m not in a chamber group or a chamber setting. I tend to stay to myself. Be polite to everyone around you, but stay in your own mental space so you aren’t exuding too much energy, and you can just stay really internalized with what you are going to say and how you’re going to present yourself onstage.

Right before I go onstage, I always tell myself, “No matter what happens– no matter if the lights go out or you forget everything or a disaster happens– nobody’s going to die. We’re just making music and we’re all here to share that music with other people.” If I can just remind myself that I do it because I love performing and I love telling a story to people, and I’m there to move an audience and I’m not there to perform for myself– that kind of removes this element of ego from the performance and it helps me have a lot more perspective in what I’m doing and what I’m trying to say. All those hours of practice leading up to it are really just so that you can give the best voice possible to what you are expressing to the audience as you possibly can and not to be like, “Oh, look at how cool I am and what I can do!” I think removing yourself from that aspect is something that I do for myself backstage and just really think about the music and the story that it’s trying to tell and hope that it moves the audience.

Watch Dawn and Lydia apply these tips at our final Young Artists Program concerts on June 27 and June 28, 2019! Both performances take place at 8pm in The Big Barn.

Music No Boundaries: NYC 2019

Music No Boundaries: NYC 2019

May 27-29, 2019

Yellow Barn Music Haul's third annual trip to NYC spanned three days of performances in Manhattan and Queens with 14 musicians performing on street corners, in neighborhood plazas, and at city parks.

Titled “Music No Boundaries: New York City,” Seth Knopp’s programming included performances of Schumann's Carnival and Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire, as well as a midday performance dedicated to Bach's cello suites.

See below for the list of performers and the full schedule of locations and programs.

MUSICIANS AND ENSEMBLES

Natasha Brofsky cello

Julia Bruskin cello

Matthew Chen cello

Emi Ferguson flute/piccolo

Jean-Michel Fonteneau cello

Tomer Gewirtzman piano

Romie de Guise-Langlois clarinet/bass clarinet

Matthew Katz cello

Seth Knopp piano

David McCarroll violin/viola

Angela Park cello

Astrid Schween cello

Lucy Shelton voice

Aaron Wolff cello

Sound Engineer: Dev Ray

Stage Managers: Michael Bradley Cohen and Christopher Grant

PARTNERS

Yellow Barn is grateful to the following people and associations for making this tour possible:

Kurt Cavenaugh and the Flatiron/23rd Street Partnership

Phil Gordon and the Lincoln Square BID

Andrew Ronan, Community Partnerships, NYC DOT

Full Schedule

Monday, May 27

7–9pm

Diversity Plaza, Queens

Robert Schumann: Carnival

Tomer Gewirtzman, piano

Arnold Schoenberg: Pierrot Lunaire (Moonstruck Pierrot)

Performed in English

Lucy Shelton, Sprechstimme; Emi Ferguson, flute/piccolo; Romie de Guise-Langlois, clarinet/bass clarinet; David McCarroll, violin/viola; Jean-Michel Fonteneau, cello; Seth Knopp, piano

Tuesday, May 28

11am–2pm

Corona Plaza, Queens

J.S. Bach: Complete Suites for Solo Cello

Natasha Brofsky, Julia Bruskin, Matthew Chen, Jean-Michel Fonteneau, Michael Katz, Aaron Wolff

6:30–8:30pm *New start time

Plaza33, Manhattan

Robert Schumann: Carnival

Tomer Gewirtzman, piano

Arnold Schoenberg: Pierrot Lunaire (Moonstruck Pierrot)

Performed in English

Lucy Shelton, Sprechstimme; Emi Ferguson, flute/piccolo; Romie de Guise-Langlois, clarinet/bass clarinet; David McCarroll, violin/viola; Jean-Michel Fonteneau, cello; Seth Knopp, piano

Wednesday, May 29

11:30–2:30pm

Richard Tucker Park, Manhattan

J.S. Bach: Complete Suites for Solo Cello

Natasha Brofsky, Matthew Chen, Jean-Michel Fonteneau, Michael Katz, Angela Park, Astrid Schween, Aaron Wolff– Complete Suites for Solo Cello by J.S. Bach

7-9pm

Flatiron South Plaza, Manhattan

Robert Schumann: Carnival

Tomer Gewirtzman, piano

Arnold Schoenberg: Pierrot Lunaire (Moonstruck Pierrot)

Performed in English

Lucy Shelton, Sprechstimme; Emi Ferguson, flute/piccolo; Romie de Guise-Langlois, clarinet/bass clarinet; David McCarroll, violin/viola; Jean-Michel Fonteneau, cello; Seth Knopp, piano

In Memoriam Janet Wells (1928-2018)

It is with deep sadness that we write with news that Janet Wells passed away on Saturday in the home that she shared with David, her partner in love and music. Janet was always truly herself with all who knew her; a unique mixture of passion and devotion, directness and mischievousness. The life force was so strong in Janet. She reveled in her joys: family, music, and always David; and heartbreak she met with even more heart. All that Janet was will continue to live through the beautifully human legacy that she and David left to all of us in Yellow Barn. It is one that could only have come from them, and one that will always bear the beauty of their spirit.

Janet would have been 90 years old this coming December. Next June there will be a celebration of her life at her and David's beloved barn and home. In the meantime, we share Janet's obituary, composed by her grandchildren, and one of David and Janet's beloved performances.

—Seth Knopp and Catherine Stephan

Janet Elaine Wells (née Rosenthal), was born in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania in 1928, and ended her life peacefully in the presence of family at her beloved home in Putney, Vermont on October 27, 2018. She would tell all who knew her (and many who didn’t) that she spent most of her life in two towns that both began with “P-U” and ended in “N-E-Y”. She shared endless stories of her vibrant, precocious childhood on a Pennsylvania block in post-war America, opening a vivid window into a different time. She began her undergraduate degree at the young age of 16 at Case Western Reserve University, after which she moved to New York and completed her Masters degree at the Teachers College at Columbia University. Janet studied with Isabelle Vengerova and Nadia Reisenberg in New York and would later hold affiliations with the Julius Hartt School of Music, Windham College, and the Brattleboro School of Music. Janet’s life was devoted to her prodigal gift of classical piano, which she excelled in since starting at the age of 5, and her beloved husband, David Wells (1927-2012). Her other loves were based in this union: her two sons, her three grandchildren, her home in Putney, and her slew of cocker spaniels. After moving to Putney in 1968, Janet and David started Yellow Barn in 1969, a source of great joy for them both for many years. Janet was lucky to have cultivated long lasting, deep friendships over several decades in her beloved Putney community, many of whom were able to visit her in the last days and weeks. The legacy of Janet and David Wells lives on through Yellow Barn, their son Dana, their three grandchildren Nikolai, Kira, and Louisa, and the loving memories held by every musician and friend who experienced their magnanimous presence and friendship. The grandchildren would especially like to thank Janet’s friend Rick for his kind help and her amazing caregivers over the last six years: Kim, Mary, Patty, Carolyn, Samantha, Almut and Donna; you all made an enormous impact on her final years. We will be organizing a celebration of Janet’s life in late spring to early Summer 2019 at the Wells’ beloved barn in Putney.

Atamaniuk Funeral Home will be handling the funeral arrangements. To sign an online register book or send messages of e-condolence to the family please visit www.atamaniuk.com.

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made in her name to Yellow Barn, PO Box 507 Putney VT 05346

"The Seven Last Words"

On Saturday, August 4th at 12:30pm, Yellow Barn will give a performance of Haydn's The Seven Last Words of Christ, interspersed with Mark Strand's poems read by Eric Bass. The poetry is printed below. In 2003, The Brentano Quartet commissioned these poems to accompany Haydn's profound work. Of this work and their commission, violinist Mark Steinberg wrote:

The Seven Last Words comprises an introduction, seven slow movements corresponding to the seven words, and a musical depiction of the earthquake following the crucifixion. It exists in several versions: for orchestra, for orchestra and chorus, and for string quartet by Haydn, as well as a reduction for piano which was approved by the composer. Of these, the arrangement for string quartet has a particular purity and intimacy in which the flexibility and subtlety of the string instruments’ sound serves to enhance the vulnerability of the expression. It is a dark and deeply moving work inspiring searching contemplation. Mostly homophonic, with melodic lines supported by simple accompanying figures, the piece explores and reveals within this elemental texture the emotional resonances inherent in the story of the crucifixion. The music is often stark, barren and painful, but always overwhelmingly human. Strength and frailty, grief and acceptance, bewilderment and understanding are all expressed with the greatest economy of means and intensity of gesture. The work serves as a meditation on the gravity of tragedy, as well as on the possibilities of hope and redemption. It is music of great weight as well as great transparency, coupling profound directness of affect with ennobling humility.

In striving to create a performance which was suited to our feelings about the work, as well as to performance outside of a strictly religious venue, we decided to commission poems to be read before each of the slow movements, one poem for each of the Words. Our hope was to find a poet whose work shared certain important aesthetic qualities inherent in the Haydn. The poems were to be secular rather than specifically religious, based on the universal human qualities evident in the story of the crucifixion and in the music. There needed to be a sense of penetrating insight and of deep feeling, setting up a dialogue between word and music. The poetry of Mark Strand shares with the Haydn a surface of relative simplicity betraying underneath a piercing understanding of the human spirit. His is poetry which is quite musical in its cadence, lending itself to well to being read aloud. There is a complete lack of pretense in his poetry, which has the sincerity so immediately apparent in the Haydn. Mark Strand is a beautiful and wise artist, and it has been an immense privilege to collaborate with him and to feel part of the genesis of a rich and affecting set of poems.

—Mark Steinberg

Mark Strand

The Seven Last Words

1

The story of the end, of the last word

of the end, when told, is a story that never ends.

We tell it and retell it — one word, then another

until it seems that no last word is possible,

that none would be bearable. Thus, when the hero

of the story says to himself, as to someone far away,

‘Forgive them, for they know not what they do,’

we may feel that he is pleading for us, that we are

the secret life of the story and, as long as his plea

is not answered, we shall be spared. So the story

continues. So we continue. And the end, once more,

becomes the next, and the next after that.

2

There is an island in the dark, a dreamt-of place

where the muttering wind shifts over the white lawns

and riffles the leaves of trees, the high trees

that are streaked with gold and line the walkways there;

and those already arrived are happy to be the silken

remains of something they were but cannot recall;

they move to the sound of stars, which is also imagined,

but who cares about that; the polished columns they see

may be no more than shafts of sunlight, but for those

who live on and on in the radiance of their remains

this is of little importance. There is an island

in the dark and you will be there, I promise you, you

shall be with me in paradise, in the single season of being,

in the place of forever, you shall find yourself. And there

the leaves will turn and never fall, there the wind

will sing and be your voice as if for the first time.

3

Someday some one will write a story set

in a place called The Skull, and it will tell,

among other things, of a parting between mother

and son, of how she wandered off, of how he vanished

in air. But before that happens, it will describe

how their faces shone with a feeble light and how

the son was moved to say, ‘Woman, look at your son,’

then to a friend nearby, ‘Son, look at your mother.’

At which point the writer will put down his pen

and imagine that while those words were spoken

something else happened, something unusual like

a purpose revealed, a secret exchanged, a truth

to which they, the mother and son, would be bound,

but what it was no one would know. Not even the writer.

4

These are the days when the sky is filled with

the odor of lilac, when darkness becomes desire,

when there is nothing that does not wish to be born.

These are the days of spring when the fate

of the present is a breezy fullness, when the world’s

great gift for fiction gilds even the dirt we walk on.

On such days we feel we could live forever, yet all

the while we know we cannot. This is the doubleness

in which we dwell. The great master of weather

and everything else, if he wishes, can bring forth

a dark of a different kind, one hidden by darkness

so deep it cannot be seen. No one escapes.

Not even the man who saved others, and believed

he was the chosen son. When the dark came down

even he cried out, ‘Father, father, why have you

forsaken me?’ But to his words no answer came.

5

To be thirsty. To say, ‘I thirst.’ To be given,

instead of water, vinegar, and that to be pressed

from a sponge. To close one’s eyes and see the giant

world that is born each time the eyes are closed.

To see one’s death. To see the darkening clouds

as the tragic cloth of a day of mourning. To be the one

mourned. To open the dictionary of the Beyond and discover

what one suspected, that the only word in it

is nothing. To try to open one’s eyes, but not to be

able to. To feel the mouth burn. To feel the sudden

presence of what, again and again, was not said.

To translate it and have it remain unsaid. To know

at last that nothing is more real than nothing.

6

‘It is finished,’ he said. You could hear him say it,

the words almost a whisper, then not even that,

but an echo so faint it seemed no longer to come

from him, but from elsewhere. This was his moment,

his final moment. “It is finished,” he said into a vastness

that led to an even greater vastness, and yet all of it

within him. He contained it all. That was the miracle,

to be both large and small in the same instant, to be

like us, but more so, then finally to give up the ghost,

which is what happened. And from the storm that swirled

a formal nakedness took shape, the truth of disguise

and the mask of belief were joined forever.

7

Back down these stairs to the same scene,

to the moon, the stars, the night wind. Hours pass

and only the harp off in the distance and the wind

moving through it. And soon the sun’s gray disk,

darkened by clouds, sailing above. And beyond,

as always, the sea of endless transparence, of utmost

calm, a place of constant beginning that has within it

what no eye has seen, what no ear has heard, what no hand

has touched, what has not arisen in the human heart.

To that place, to the keeper of that place, I commit myself.

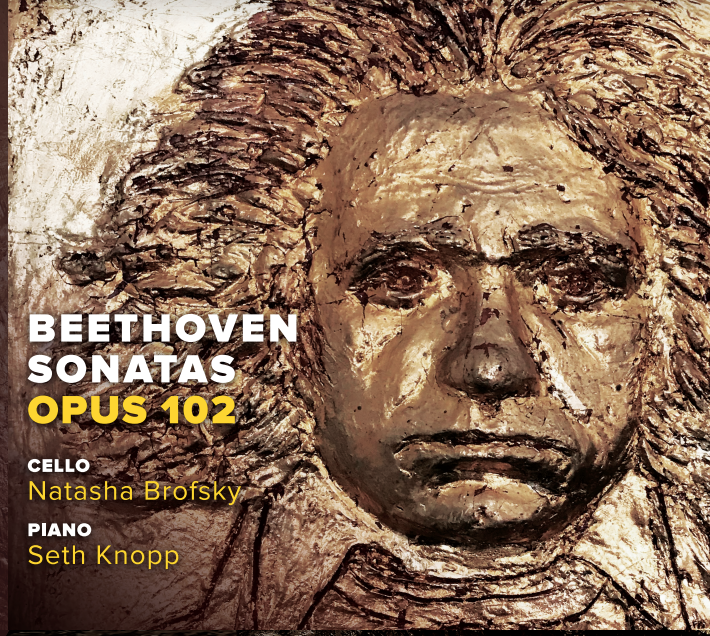

Beethoven Sonatas Opus 102

Yellow Barn is pleased to announce the arrival of faculty member Natasha Brofsky's recording of Beethoven's Opus 102 sonatas for cello and piano, which she recorded with Seth Knopp as part of a long personal journey with these pieces. A glimpse of her musical exploration can be found in her liner notes below.

Beethoven Sonatas Opus 102 is available online and at Yellow Barn summer concerts.

The terrible fire that consumed Count Rasumovsky’s palace in 1814 caused the palace’s famed resident quartet, the Schuppanzigh, to disperse to find new work. As a result, the quartet’s cellist, Joseph Linke, spent the summer of 1815 with Beethoven’s great friend and supporter, the Countess Marie Erdödy, at the Erdödy summer residence at Jedlesee. The Countess, though an invalid, was a fine pianist. As for Linke, he was a superlative performer. According to his obituary, published in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musikin 1837, his musical interpretations could be variously ‘flattering, capricious, passionate and so on, his playing capturing the critical essence of Beethoven’s music’.1No wonder Beethoven was lighthearted and joyful in his letters to the Countess - letters in which he contemplated the prospect of visiting Jedlesee and bringing with him the new sonatas he had just composed.2

Years later, a reviewer for the Berliner Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung1 (1824) would praise these sonatas as a “a work of the newest inspiration of our great master. It is not necessary to say that, like all his works, its originality distinguishes itself not only from all products of other composers, but also, remarkably enough, from his own works. Everywhere the inexhaustible source of his glowing genius pours out, fresh and bright, a new outburst of his feelings, and with each new gift one must admit after repeated hearings not only its beauty, but novelty, as something previously unheard from him and, naturally, from others.”3

In a gradual process that began with Beethoven’s earliest trios and sonatas, the emancipation of the cello from the left hand of the piano is fully realized in Opus 102, making the cello an independent voice in the musical conversation.

Sonata No.1 in C Major

In the autograph of the opening of the C Major sonata, the word teneramente(tenderly) is written in large letters in Beethoven’s hand. In the printed score, it is none so prominent, although perhaps it should be; for throughout his life, Beethoven increasingly used descriptive words in his scores. The reason is implicit, perhaps, in the commentary of Ferdinand Ries, who studied piano with Beethoven: “If I made a mistake in passages or missed notes and leaps which he frequently wanted emphasized he seldom said anything; but if I was faulty in expression, in crescendos, etc., or in the character of the music, he grew angry because, as he said, the former was accidental while the latter disclosed lack of knowledge, feeling, or attentiveness.”4

In the title of the C Major Sonata, Beethoven originally wrote “free sonata,” seemingly conceiving ofthe pieceas unbound by traditional forms. The words are a reminder that Beethoven was celebrated in his time as a great improviser. As in his Sonata in A MajorOpus 69, he opens the C Major with the cello alone, improvising, as it were, on a C Major scale. The simplicity and inventiveness here are remarkable. The piano joins the cello on the last three notes of this opening phrase with a mini-scale of its own, as if playfully commenting on the cello’s scales while also harmonizing the descending motive. Famously, the motivic material for the entire sonata is derived from this opening phrase. In the Andante sections of the work, the instruments seem to be improvising together with a sense of freedom and timelessness. In contrast, the a minor Allegro vivace movement, which follows the opening Andante, is compact and driving. The Adagio, originally intended to follow without pause, begins with a whimsical cadenza as if the pianist is ruminating on the opening motives of the piece. The cello answers, taking us into a dark and mysterious mood. It is only after a succession of stormy and troubled crescendos that Beethoven gives us the most tender phrase of the piece. Then, like a memory that has been embroidered in its retelling, the opening Andante returns in a more ornamented form. The final Allegro vivace is a playful, boisterous and virtuosic movement. It provides a vivid example of Beethoven's genius in portraying a huge range of emotion while achieving compositional unity.

Sonata No.2 in D Major

The D Major Sonata has the more standard three-movement form. Like the a minor Allegro vivace of the C Major Sonata, the first movement is not only terse, but also full of dramatic contrasts as well as beautiful lyrical moments. The second movement begins with a soft and sad hymn in minor with a touch of major harmony that brings a glimmer of hope. The music of the middle section of the movement is tender and lovely, made all the more fragile because it is preceded by music that is so unsure and searching. Beethoven returns to an improvisatory quality with the harmonic wanderings at the end of this glorious slow movement. The famous fugue that is the third movement of this work begins with the playful trading off of a one octave scale. This coy dialogue was added by Beethoven after he completed the whole movement. From this simple scale he creates a fugue subject, and as each voice enters, the fugue becomes a riotous cacophony.The dissonance of this third movement was challenging for Beethoven’s audiences; it still sounds modern, even in the 21stcentury.

This recording represents only a snapshot of our lifelong effort to capture the spirit and essence of Beethoven’s music. While playing together in the Peabody Trio for nearly two decades, we performed all of the Beethoven Trios. In addition, we played the Cello Sonatas and coached our students on these pieces. In grappling with these works over many years, we have become increasingly familiar with the medium and ever more obsessive about the ways in which our instruments speak to each other in Beethoven’s music. The instruments sing together, argue, reminisce, shout, and weep. These Sonatas have challenged us to use our utmost imagination in color and expression. It is this challenge that has inspired us to come back to these pieces over and over, to explore them again and again.

1 Neue Zeitschrift für Musik6 (1837), 130 (21 April) as quoted in Moskovitz, Marc D.; Todd, R. Larry. Beethoven's Cello: Five Revolutionary Sonatas and Their World (Boydell & Brewer Group Ltd. Kindle Edition), Kindle Locations 4521-4522.

2 This sequence of events is detailed in Moskovitz, Marc D.; Todd, R. Larry. Beethoven's Cello: Five Revolutionary Sonatas and Their World

3 Berliner Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung1 (1824), 409– 10 (1 December) as quoted in Moskovitz; Todd. Beethoven's Cello: Five Revolutionary Sonatas and Their World, Kindle Locations 6233-6238.

4 Ries, Ferdinand; Wegeler Franz. Biographische Notizen über Ludwig van Beethoven(Coblenz 1838), p. 94 as quoted in Thayer’s Life of Beethoven, ed. Elliot Forbes, editor(Princeton University Press, 1967), p. 295.