PMA extends Beethoven Walks through Labor Day

A young naturalist enjoys Beethoven Walks

Beethoven Walks at Hannum Trail on Putney Mountain has been extended through Labor Day!

This is one of a series of Beethoven Walks, which incorporate reproductions of Beethoven’s sketches, or leaves from his autograph manuscripts, connecting those walking the path with Beethoven’s music, his creative process, and the inspiration he drew from nature. Now both the Hannum Trail and the Greenwood Trail on the Greenwood School campus will remain open throughout the season. Both are free and open to the public.

In March 2020, when the coronavius pandemic escalated, Artistic Director Seth Knopp contacted the Putney Mountain Association to discuss potential sites for Beethoven Walks. The Hannum Trail was jointly selected not only for its beauty and remoteness, but also for its "chapters", which lend themselves naturally to different works by Beethoven.

Due to an outpouring of enthusiasm and many requests from those who have heard about but not yet been able to visit the Hannum Trail, the Putney Mountain Association is generously allowing more time for people to enjoy it, for which Yellow Barn is deeply grateful. People who have walked the trail have expressed feeling transported, and shared that it is the first time since the pandemic escalated that they have been able to put it out of their minds. Some of the comments we have received include:

We felt the beauty and wonder of the time, place, and artistry of this creation. The walk is a masterpiece.

Amazing, inspiring.

What an awesome experience! I don't know where to begin - I'll never hear that music the same way again, and I've never experienced the forest and its noises, silence, and

movement in that way before.

While in the forest I think I forgot about the pandemic for the first time since it started…which is really saying something.

More information about the Beethoven Walks, and how to download apps with specifically-programmed music associated with each trail, are here.

On the Bach Cello Suites

In advance of Yellow Barn's performances of the complete Bach Cello Suites, alumna cellist Annie Jacobs-Perkins reflects upon Bach's role in our lives today.

Part I: Suite No.1, Suite No.4, and Suite No.5 (July 16)

Part II: Suite No.2, Suite No.3, and Suite No.6 (July 18)

Only two portraits exist of J.S. Bach. In both canvases he stares at his audience, controlled and austere. Rather little is known about the man in these portraits. On one hand, historians know the cities where he lived, the years he lived there, and the people for whom he worked and with whom he lived. On the other hand, very little exists in the way of private correspondence and anecdotal knowledge. Small glimpses and clues into the lives of famous artists are treasured by performers and audiences as a way of making these men and women relatable. Unlike composers such as Beethoven, Brahms, and the Schumanns, Bach’s self-represented voice exists only in his music.

When listening to Bach’s music, one immediately thinks of the intersection of logic, function, and spirituality. Although these traits often conflict, as the Bach scholar Christoph Wolff writes, one can “[understand] his art as a paradigm for reconciling what would ordinarily be conflicting stances.”

Today, Bach swamps social media during the COVID-19 pandemic. Musicians post daily Bach videos, pictures of solo driveway performances for their neighborhood, meaningful recordings by favorite artists, livestreamed entire suites, partitas, and sonatas from their apartments. This is for a variety of reasons—the first being that Bach is responsible for a large and unprecedented body of solo instrumental music. The second, and rather more important reason, is that the architecture and craftsmanship in Bach’s music is reassuring to a world with an unclear future and irreparably shaken trust.

The Bach Cello Suites were written around 1720, during which time Bach lived in Cöthen under the employment of Prince Leopold. It was during his employment in the Cöthen court from 1717 to 1723 that Bach wrote secular, solo instrumental music. Prince Leopold valued the arts greatly, and Bach enjoyed a prosperous and harmonious relationship with his employer until Leopold’s marriage led Bach to seek new employment in Leipzig.

Also in 1720, Bach lost his first wife. At the time of her death he was away from home on business and did not return until after her burial. He married again in 1721, to the then twenty-year-old Anna Magdalena Wilcke.

Anna Magdalena plays an important role in the history of the cello suites. A highly skilled soprano and copyist in her own right, she brought her musical skills to her marriage. No original manuscript survives in Bach’s own hand of the cello suites. The two most reliable primary sources are Anna Magdalena’s copy made between 1727 and 1730 and Johann Peter Kellner’s, another noted copyist of the time. Because of her proximity to the original source, and because Kellner’s manuscript is incomplete, historians agree that Magdalena’s is the most reliable copy.

Possibly because so little personal information exists on this man so beloved for his music, and because husband and wife, as well as their ten surviving musical children (between his two wives, J.S. Bach fathered twenty children, ten of whom survived to adulthood) joyfully benefited and took inspiration from each other, the Bach family’s lives have been fabricated and imagined in myriad sources. In 1890, the author Elise Polko conjured a domestic scene in the Bach household: Anna Magdalena sitting with a three-year-old son on her knee at the table, C.P.E. showing his father compositions and asking for his opinion, J.S. Bach next to his wife, with “his black, fiery eyes [that] had an indescribable power, which was almost impossible to resist. You were compelled to look at them again and again; you felt as if you were about to learn from them something of unearthly beauty.” Other sources say that, despite his reserved portraits and piercing black eyes, J.S. Bach had a lively, even very occasionally raunchy, sense of humor; perhaps he was not always as pious as those austere portraits suggest.

In the end, it does not matter. The most trying and beautiful part of Bach’s music is that, even with all its logic, it cannot be explained. It is so easy to assign personalized human emotions to the man and his family, try to make his heavenly music somehow more explicable. The best one can do is listen with wonder to his music as it is, and rather than trying to hear the man behind the music, listen in awe to the gift he gave the world.

—Annie Jacobs-Perkins

Week Three at YAP

Yellow Barn's 2020 Young Artists Program, our first distance learning program, might have finished for the time being, but the work explored and the connections made are strong enough to carry us to next June, when we look forward to welcoming every musician in this year's program to join us in Putney—at long last.

In their last week, participants had the opportunity to speak with composer Lei Liang, currently residing in California where he is on the faculty of the UC-San Diego, one more example how this year's program gave participants the rare opportunity to work with faculty and guest faculty from across the United States and abroad.

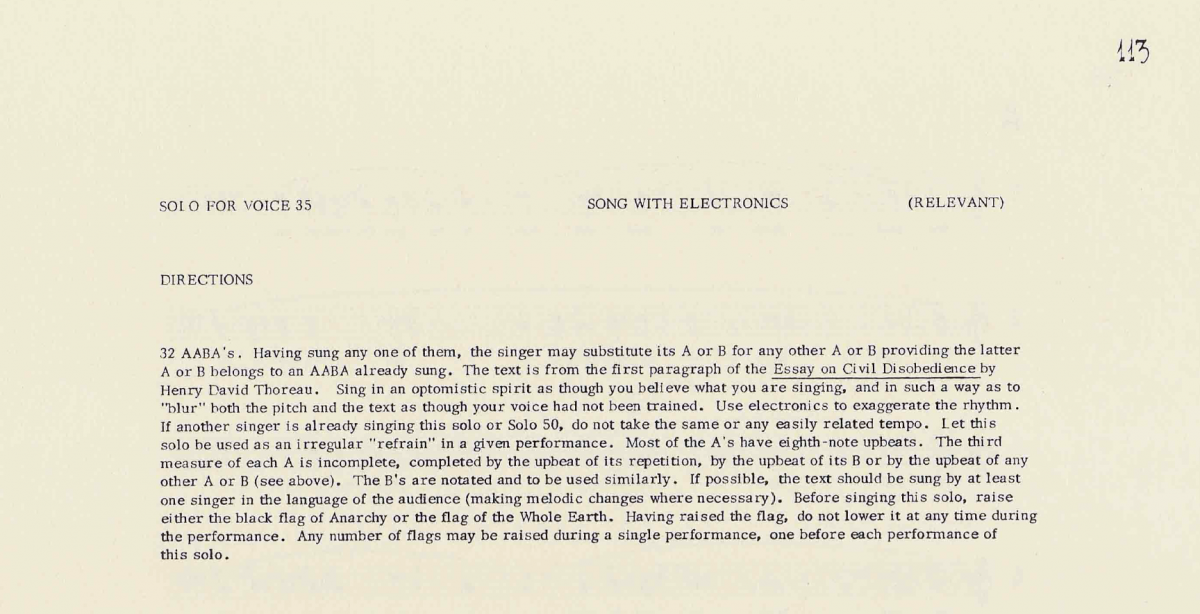

Most of all, the final week included a marathon of performances ranging from solo performances of works for musicians and electronic tape, world premeires of new works by YAP composers created during the program, and the conclusion of this year's John Cage Songs project, which gave all of us a unique look into the lives of YAPpers in their natural habitats! Over 81 performances,took place during YAP this year, including four new solo works from each of the six composers.

Four of these performances are included below, and many more will be appearing on social media in the coming days. Enjoy, and look forward to seeing more of these inspiring musicians next summer.

Mark Applebaum: Aphasia

Nupur Thakkar (Schumburg, IL)

Mario Davidovsky: Synchronisms No.3 for cello and electronic sounds

João Pedro Gonçalves, cello (Lisbon, Portugal)

John Cage: Song #35

Rolando Gómez (Princeton, FL)

Press for Yellow Barn Opening Night 2020

Cashman Kerr Prince wrote about Yellow Barn's 2020 Opening Night Concert in the Boston Musical Intelligencer, published on July 11, 2020.

Gilbert Kalish (Photo: Zachary Stephens)

Traveling to bucolic landscapes and enjoying the wealth of music in more relaxed music festivals provides one of the main joys of New England summertime. This year we cannot visit this barn in the Vermont woods (or many other sites), but they are nevertheless finding ways to transmit some measure of that joy to us.

Gilbert Kalish began yesterday’s Yellow Barn stream by speaking about Charles Ives and his mighty sonata on local thinkers. In some dozen minutes Kalish made a case for Ives as the first American classical composer, one knowledgeable of European classical music traditions but steeped in American music, with the music of his father’s band encoded in his compositional DNA. At the same time, Ives wrote about his understandings of the Transcendentalists who populate this sonata. Kalish tied Ives to this year’s celebrated composer, Beethoven, noting that the opening four notes of that now-ubiquitous symphony recur some 40 times in Ives’ sonata. (He invites us not to listen for it and says as a performer he finds that it distracts from the music at hand to stumble across another citation of Beethoven while in Concord.) Visually, Beethoven looms as a presence, with enlarged autograph pages of his String Quartet Op. 132 on the walls at the back of the stage.

Then to the music. Kalish humbly said he was going to try to play Ives’s Concord Sonata. And play he did. Dating from circa 1911 – 1915, Ives’ “Piano Sonata No. 2 ‘Concord, Mass., 1840-60’” is a monument in four movements. The first, “I. Emerson,” begins meditatively, calmly and quietly. While the tempo remains ruminative, the music becomes increasingly complex (if not, indeed, thorny). There is a tolling, bell-like quality which Kalish perfectly captured; perhaps Ives bethought himself momentarily of Amherst, Mass. and Emily Dickinson at the end of this movement? The second movement, “II. Hawthorne,” opens more chipper and melodic; we move from essays to longer prose narrative. I am astounded at the carefulness and variety of touch Kalish extracted using the wooden block for the black-key tone clusters. In this movement the American songs and hymns Kalish alluded to earlier come to the fore, as citations, as inspiration, as irruptions into the musical text (earworms of centuries gone by, perhaps)—notably dances that sound almost-familiar. These musical stories whirl frenetically into a dance of excitement, then a breather, and it commences to build up again. “III. The Alcotts” opens with bell-like pedal tones; church bells seem a structurally uniting refrain throughout. (I am not sure Bruce Hornsby had that quite in mind in his 1986 citation of this movement’s opening.) The Alcotts try on a waltz, later a jig, before returning to a quiet conclusion. The concluding movement, “IV. Thoreau,” tackles everybody’s favorite Transcendentalist, in a deliberate way, full of quiet introspection. Here the optional flute part appears, at first as though a febrile manifestation then gaining strength in its off-stage presentation. The sonata finds its conclusion in quiescence and stillness. Screen fades to black.

Harmonically this sonata is fresh and varied, ranging from the familiarity of common practice to Ives’s own new explorations, often in many different directions over the length of this work. Uniting these movements is a shared sense of the Promethean task of creation, its rewards and its struggles, and here expressed in the context of a young nation striving to find its own artistic path forward, in Concord and in Connecticut.

Following a ten-minute intermission, the concert resumed with the world première of Stephen Coxe’s “Entstehung Heiliger Dankgesang (Emergence of a Holy Song of Thanksgiving)” (2020). Composed for string quartet and percussion, this work is a response and a prelude to the slow movement of Beethoven’s Op. 132 quartet, which follows it on this program. Alice Ivy-Pemberton and Emma Frucht, violins; Roger Tapping, viola; Coleman Itzkoff, cello; and Eduardo Leandro, percussion brought Coxe’s music to life. Here is Coxe on his work:

The current work consists of 45 pages of realizations, reworkings, responses, guidelines for interpretation, and examples from Beethoven’s autograph score, all of which may be excerpted and arranged in any fashion for a given performance. A performance of the entire set would take well over an hour: this evening’s performance explores a considerably shorter ‘excerpted’ version among many possible versions, as it is conceived to directly precede a performance of the Op.132 slow movement.

This aleatoric work encompasses four types of response: canons, realizations, guidelines, and “roads not taken” but discernible in manuscript pages. You can read Coxe’s full note HERE. Here beginning with bowed percussion and the clarion quality of such sounds, the music intones its introit. The string players pursue thoughts and themes; the percussionist stands in for the scribbling composer. Again, music attempts to capture the act of creation at work and at play. The whole has an ethereal quality to it which underscores and reinforces the improvisatory nature of the composition and is so perfectly captured in this performance.

The same string players (now minus percussionist, who quietly left the stage) presented “Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit, in der lydischen Tonart,” the slow third movement from Beethoven’s String Quartet in A Minor, Op. 132 (1825). Opening quietly and drawing on the tradition of hymns, which it enriches and ennobles, this music builds in intensity and passion as it reifies and affirms its own act of artistic creation. Between moments of hymn and canon with the religious intensity we associate with the pinnacle of those forms, and reinforced by invoking the piety so often heard in the harmonic Lydian modality here used, there come moments of lighthearted charm that recall trios of Haydn quartets. Tripartite structure predominates yet the signification shifts as the music reprises, reflecting thematic growth as thanks profuse. Sacred and secular, this music twirls around twin and often disparate poles of daily life; we hear Beethoven grappling to express his own testament. The movement ends with the diminishing waves of harmonious sound, never disappearing only growing fainter as they ripple outwards into the universe.

With two cameras and an unknown number of microphones (greater than four that I saw over the course of the broadcast), Yellow Barn has invested in bringing us an enriching experience of the music on their campus. Gone is the intimacy, of course, and there are some glitches — some audio pops, but clear video. (I watched on a newer tablet.) Early in the Ives, the audio briefly took on the quality of a music box. I file this under the Law of Unintended Consequences. Ives would, I think, have loved it. This is one positive addition to the experience that comes from these newer modalities of delivery. For the second half, the musicians spread out, standing throughout the barn for Coxe’s work, reading from notes and sketches on the walls and somehow incorporating themselves into the décor along with the reproduction of Beethoven’s manuscript pages for the op. 132 quartet. For the Beethoven the quartet of strings took to a more canonical seated arrangement yet at greater than normal distance one from the other.

The initial live presentation on Friday night had to be postponed until Saturday afternoon due to connectivity issues in southern Vermont. Still, this performance rewarded our wait — and I hope it will remain available for some time. Find a spot in your garden, equip yourself with a cool beverage of choice, tune in HERE, and if your luck prevails, perhaps some garden birds will opine on the musical birdsong in this fabulous opening Yellow Barn concert, to complete the idyll we crave.

Cashman Kerr Prince, trained in Classics and Comparative Literature, is now a Visiting Scholar in the Department of Classical Studies at Wellesley College. He is also a cellist of some accomplishment, currently playing with the Brookline Symphony Orchestra

Michael Gallagher's 4th of July

Yellow Barn Awarded NEA Cares Act Grant

Margaret Grayson wrote about Yellow Barn's NEA Cares Act grant, published on July 3, 2020.

Ten Vermont arts and culture organizations received more than $600,000 in direct grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and National Endowment for the Humanities, as part of the federal coronavirus relief package.

The NEA awarded $50,000 grants to Kingdom County Productions, Dorset Theatre Festival, the Vermont Folklife Center, the Community Engagement Lab, the Yellow Barn and the Weston Playhouse Theatre.

The NEH awarded $133,512 to the Vermont Historical Society, $69,263 to the University of Vermont, $29,362 to the Henry Sheldon Museum of Vermont History, $53,036 to the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum and an additional $97,017 to the Folklife Center.

The Weston Playhouse, Vermont’s longest-running professional theater, has lost all of its earned income since canceling its summer theater season, said executive artistic director Susanna Gellert. While the theater has been able to reduce its operating budget from $2.3 million annually to about $1 million, the grant support is still vital.

“The $50,000 NEA grant is a pretty huge leg up for us,” Gellert said. She said the Weston staff are planning to use it to budget for the 2021 fiscal year, which begins January 1. A Paycheck Protection Program loan ensured that no staff have been laid off so far, and Gellert is cautiously optimistic that donor support will remain strong enough that all staff can be retained.

The theater’s director of development, Emily Schriebl Scott, said planning for the future is about more than just financial concerns. There are more philosophical questions, too: What should a theater try to be during a pandemic? For the Weston, staff have focused on supporting playwrights and artists in creating new work and virtual offerings.

“It’s been really heartening to land on these incredibly creative ways of moving forward,” Schriebl Scott said.

The federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act awarded $75 million each to the NEA and NEH, 40 percent of which was distributed to statewide organizations such as the Vermont Arts Council and Vermont Humanities to distribute further. Those two organizations have been distributing $700,000 from the NEA and NEH in the form of grants to nonprofits of between $2,500 and $10,000.

More than 200 organizations and individual artists have applied for grants, reporting more than $36 million in current and projected losses due to the pandemic. According to the arts council, the creative sector accounts for 9.3 percent of the state’s jobs.

The remainder of the NEA and NEH money was earmarked for direct grants. These national grants were highly competitive. The NEA received more than 3,000 applications and awarded 855 grants; the NEH received more than 2,300 applications and awarded 317 grants.

“We are incredibly grateful for everything the NEA does, and especially the arts council. But I would love to see government funding increase in this moment,” Gellert said. “We’ve talked, as a state, about how the creative economy fuels Vermont. I think we’re really going to learn what that means.

"I’m sure we will start to see some organizations have to close their doors for good," Gellert added, "and I think the impact will be profound.”