Leon Fleisher (1928-2020)

Today is the first day without our dear Leon Fleisher amongst us. We are all so fortunate to have lived during his time, to have heard the truth he spoke through his playing, and to have witnessed the courage with which he fought to speak it.

—Seth Knopp

On July 23, 2017, Yellow Barn hosted an 89th birthday gala and party for Leon. For the first half of the program, Julian Fleisher joined his father in sharing stories and music from Leon's extraordinary life with music. We share those moments now, with joy and unending gratitude.

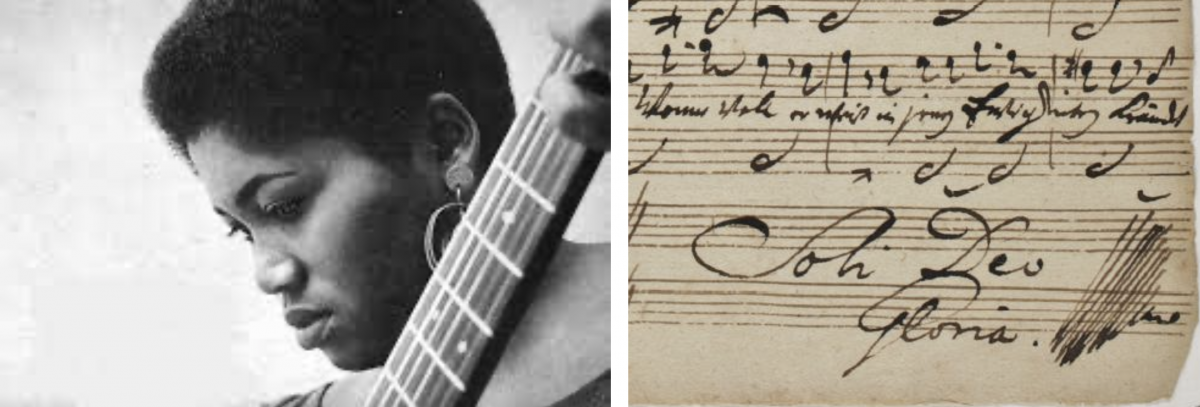

Odetta opens concert of Bach's cello suites

Odetta, with a detail of one of J.S. Bach's autograph manuscripts signed "Soli Deo Gloria" ("To the Glory of God Alone"), a dedication that the composer added to every piece of sacred music and many secular pieces as well.

On July 18, 2020, a recording of Odetta performing the spiritual "Glory, Glory" opened a concert of Bach Cello Suites at Yellow Barn. Following the concert, alumna cellist Annie Jacobs-Perkins wrote the following biographical note for Odetta:

In his letter to America penned days before his death, activist and Representative John Lewis summarized the words of Martin Luther King Jr. that meant so much to him as a young man. “He said we are all complicit when we tolerate injustice. He said it is not enough to say it will get better by and by. He said each of us has a moral obligation to stand up, speak up, and speak out. When you see something that is not right, you must say something. You must do something. Democracy is not a state. It is an act, and each generation must do its part to help build what we called the Beloved Community, a nation and world society at peace with itself” (New York Times, July 30 2020).

The folk and blues singer Odetta worked tirelessly to shape that Beloved Community. Born in 1930 in Birmingham, Alabama, she was a favorite artist of King’s and sang with him through many of the events that made him an icon in American history. She was there for the walk from Selma to Montgomery, King’s “I have a dream” speech, a civil rights demonstration for President Kennedy, and for countless other civil rights events. She is known affectionately as the “voice of the civil rights movement.” President Bill Clinton awarded her the National Medal of Arts and Humanities in 1999, and if she had not died from heart disease shortly before at age seventy-seven, Odetta would have performed at President Obama’s inauguration ceremony in 2008.

Although Odetta did not reach the huge popular success of folk artists such as Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Harry Belafonte and Janice Joplin, all of them cite her as a major influence on their work. In a Playboyinterview from 1978, Dylan said that “The first thing that turned me on to folk singing was Odetta.” Odetta’s family moved to Los Angeles when she was six-years-old, and it was at that time that she began studying voice. She trained in opera and theater at Los Angeles City College, but realized her love of folk music during extra curriculars and self-reflection.

During an interview with The New York Times, Odetta stated that the recorded work songs she heard as a very young child in Alabama had a huge influence on her music—they served as a medium to find pride in self. In addition to her important role as an activist, Odetta is remembered for being unashamedly and unabashedly herself. At a time when black women faced social pressure to straighten their hair as a symbol of white respectability, Odetta appeared in front of thousands of audience members time and time again with her hair naturally curly. She said, “You’re walking down life’s road, society’s foot is on your throat, every which way you turn you can’t get from under that foot. And you reach a fork in the road and you can either lie down and die or insist upon your life.”

Watch the July 18th concert stream in its entirety:

2020 Yellow Barn videos

Watch performances from Yellow Barn's 2020 Summer Artist Residencies in Putney, Vermont.

View programs from the 2020 Summer Season

July 10, 2020 | View program details

Charles Ives Piano Sonata No. 2 “Concord, Mass., 1840–60”

Stephen Coxe Entstehung Heiliger Dankgesang (Emergence of the Holy Song of Thanksgiving)

Ludwig van Beethoven String Quartet in A Minor, Op.132 Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit, in der lydischen Tonart (Holy song of thanksgiving of a convalescent to the Deity, in the Lydian mode)

July 11, 2020 | View program details

Anton Webern Five Movements for String Quartet, Op.5

Benjamin Britten Elegy for Solo Viola

Antonín Dvořák Bagatelles, Op.47

Frederic Rzewski To The Earth

July 16, 2020 | View program details

Johann Sebastian Bach

Suite No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1007

Suite No. 4 in E-flat Major, BWV 1010

Suite No. 5 in C Minor, BWV 1011

Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten from Cantata, BWV 93

July 18, 2020 | View program details

Glory, Glory

Johann Sebastian Bach

Suite No.2 in D Minor, BWV 1009

Suite No.3 in C Major, BWV 1009

Suite No.6 in D Major, BWV 1012

July 23, 2020 | View program details

Mario Davidovsky (1934-2019)

Synchronisms No. 3 for Cello and Electronic Sounds

Synchronisms No. 6 for Piano and Electronic Sounds

Synchronisms No. 9 for Violin and Electronic Sounds

Synchronisms No. 11 for Contrabass and Electronic Sounds

Synchronisms No.12 for Clarinet and Electronic Sounds

July 25, 2020 | View program details

John Cage Solo for Voice 39 from Song Books

Franz Schubert Ganymed, D.544

Amy Beth Kirsten yes I said yes I will Yes.

Travis Laplante The Obvious Place

Toshio Hosokawa Windscapes

Beethoven Walks at Greenwood Trail and Hannum Trail

Ludwig van Beethoven Andante from Bagetelles, Op.126 No.3 in E-Flat Major

July 30, 2020 | View program details

Stephen Coxe The Very Hungry Caterpillar

Mark Applebaum Gone, Dog. Gone!

Fredrik Andersson The Lonelyness of Santa Claus

Alan Ridout Ferdinand for Speaker and Violin

John Cage Solo for Voice 57 from Song Books

John Cage Solo for Voice 22 from Song Books

Georges Aperghis Récitation No. 9 for Female Voice

Liza Lim Inguz

John Cage Solo for Voice 23 from Song Books

Matthew Aucoin Dual

Philippe Manoury Le Livre des Claviers II

Johann Sebastian Bach Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002

Dimitri Shostakovich Seven Romances on Poems of Alexander Blok, Op.127

Osvaldo Golijov Tenebrae

James MacMillan Angel

Gone, Dog. Gone!

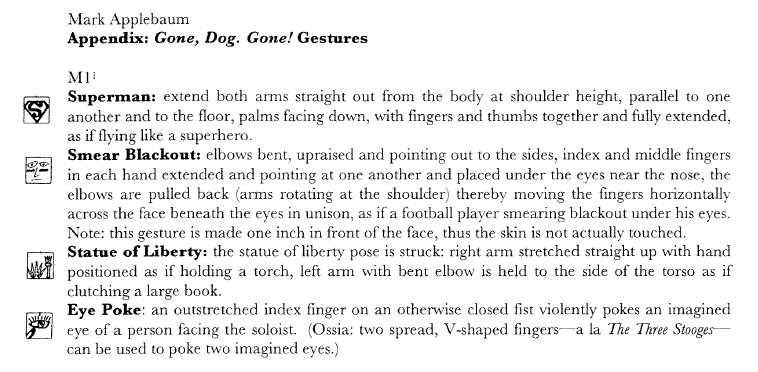

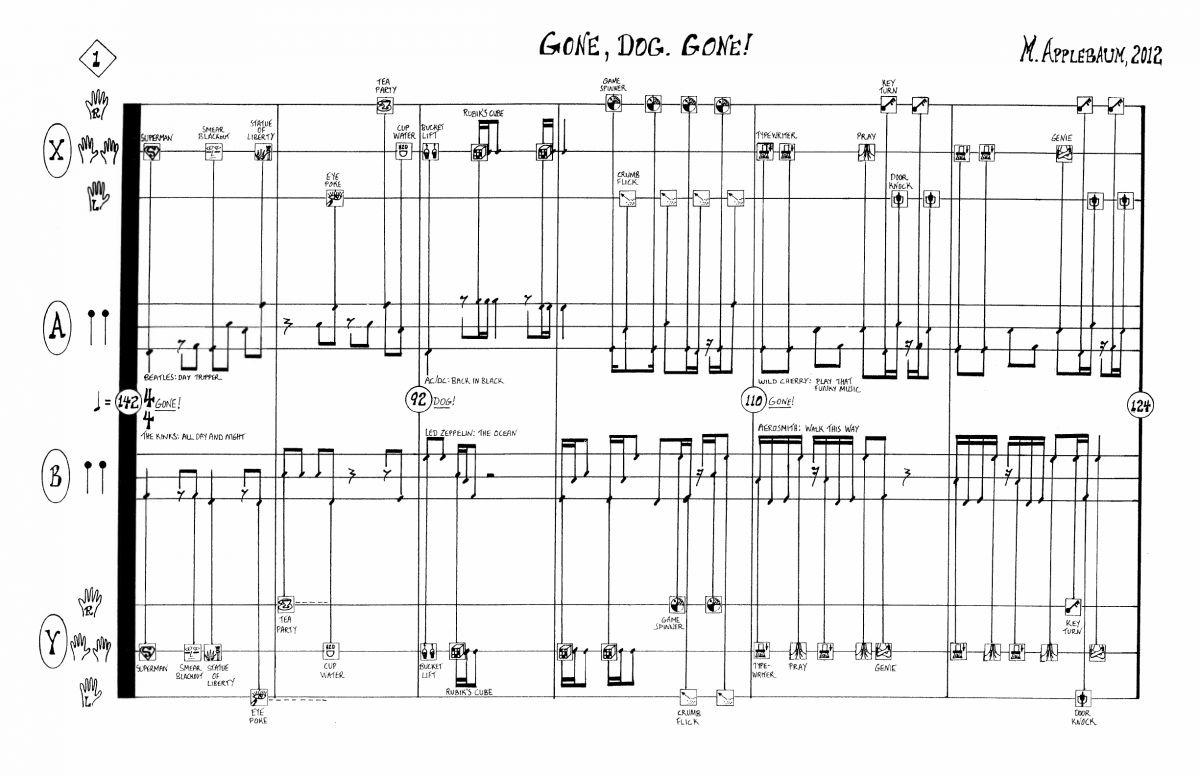

Applebaum's piece consists of two kinds of music: The sound created by eight instruments—conventional, invented, or found—and silent hand gestures. Over 80 gestures are indicated, ranging from "Thumbs Up" to "Etch A Sketch" to "Bubble Wrap". Each gesture has a symbol and detailed instructions, all of which have to be memorized and performed rapidly, with precision:

The score also referencecs source materials—28 grooves found in pop or rock pieces—which provide both rhythm and tempo. For example, the first page alone includes references to The Beatles, The Kinks, AC/DC, Led Zeppelin, Wild Cherry, and Aerosmith:

Gone, Dog. Gone! is a companion piece to Applebaum's Aphasia, a work explored by many Yellow Barn perussionists, including the four percussionists in this year's Young Artists Program. Just a few weeks ago Nupur Thakkar recorded the following performance:

On Yellow Barn's tribute to Mario Davidovsky

Kurt Gottschalk writes about Yellow Barn's tribute to Mario Davidovsky in Bachtrack, originally published on July 27, 2020.

Seth Knopp performing Synchronisms No. 6 for piano and electronic sounds

While electronic music wasn’t Mario Davidovsky’s primary focus, it is arguably his legacy. The Argentinian-born composer studied with Milton Babbit and served as associate director of the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center from 1980 to 1994. His most popular compositions remain the twelve Synchronisms for electronic tape and soloist or ensemble, five of which were presented in a streamed concert from Vermont’s YellowBarn.

Davidovsky – who died on 23th August 2019 at the age of 85 – set out to treat electronics as an equal partner to acoustic instruments in the Synchronisms, and did so in varying ways, from integrating the sounds to amplifying them to employing a sort of disembodied counterpoint. The solo-plus-tape pieces would also seem to owe much to Luciano Berio’s roughly contemporaneous Sequenzas as efforts to chronicle instrumental capacities. But unlike the cold calculations of, say, Helmut Lachenmann, the end goal for both Berio and Davidovsky was still to give the instruments something to sing. The YellowBarn portrait stuck to Davidovsky’s social distancing-friendly pieces for solo instrumentalists, although the 1992 Synchronisms no. 10 for guitar and electronic sounds was sadly left out.

Rather than a chronological presentation, the program was ordered giving the electronics a slow build from beginning to end. The sensation, especially in the first half, was often more of exploded solo than duet or accompaniment. The electronic sounds seemed to live within the instruments, sneaking out nonchalantly while other sounds were played or making a break for it and storming the gates. This, of course, had something to do with it being a stream – the acoustics of a physical space could make for a very different experience – but it was in the composition as well. During Seth Knopp’s wonderful performance of the 1970 Synchronisms no. 6 for piano and electronic sounds (for which Davidovsky won a Pulitzer Prize), the electronics worked like a reverse decay, echoing, building and stopping abruptly, mirroring and anticipating the soft percussive sounds of the clacking keys, making it almost violent, then recessing into something almost as gentle as a lamb’s dream, always in harmony. Knopp moved easily between extreme dynamics, soft and sensitive passages abutting abrupt, heavy sections.

Lizzie Burns played the 2005 Synchronisms no. 11 for contrabass and electronic sounds in a strong embrace of her instrument, poised and exacting when it seemed she should be surprised by the sounds occasionally erupting around her. Yasmina Spiegelberg was animated, playing to the room (and only the room, one would guess, the nearly empty room) in her reading of the 2016 Synchronisms no.12 for clarinet and electronic sounds. Here the acoustic sound was invaded by less natural sounds: beeps and hums and digital crickets, as well as the mimicking of her own overtones. Her body language became part of the piece; she looked anticipatory, concerned, suggesting crescendo as she played the opposite, and stopping in mid-phrase. She seemed to be the first to outsmart the extraneous sounds.

Synchronisms no. 3 for cello and electronic sounds (from 1964) toyed with the baroque (or maybe Bach has so engrained himself on the instrument that it only felt that way). It also seemed particularly demanding. Like Knopp’s execution of the piano piece, cellist Coleman Itzkoff rose to the dynamic demands well, the electronics here taking a percussive role. In the final Synchronisms no. 9 for violin and electronic sounds (1988), the electronics ran free, almost like a string quartet with Alice Ivy-Pemberton as the only string player, displaying focus and beautiful attention to detail.

The concert was presented on a simple stage in simple frames (two stationary cameras), not trying to create anything beyond the traditional concert experience, with the exception of prerecorded introductions and memorials. Soprano Susan Narucki’s touching reminiscences, for example, made for the rare occasion of a singer talking over her own performance. Davidovsky had a longstanding relationship with the Vermont venue, and had repeat residencies with the rural new music community. While the summer season was considerably, necessarily, stripped down, the organization decided to retain the planned composer portrait. Streamed performances continue through 8th August.

PMA extends Beethoven Walks through Labor Day

A young naturalist enjoys Beethoven Walks

Beethoven Walks at Hannum Trail on Putney Mountain has been extended through Labor Day!

This is one of a series of Beethoven Walks, which incorporate reproductions of Beethoven’s sketches, or leaves from his autograph manuscripts, connecting those walking the path with Beethoven’s music, his creative process, and the inspiration he drew from nature. Now both the Hannum Trail and the Greenwood Trail on the Greenwood School campus will remain open throughout the season. Both are free and open to the public.

In March 2020, when the coronavius pandemic escalated, Artistic Director Seth Knopp contacted the Putney Mountain Association to discuss potential sites for Beethoven Walks. The Hannum Trail was jointly selected not only for its beauty and remoteness, but also for its "chapters", which lend themselves naturally to different works by Beethoven.

Due to an outpouring of enthusiasm and many requests from those who have heard about but not yet been able to visit the Hannum Trail, the Putney Mountain Association is generously allowing more time for people to enjoy it, for which Yellow Barn is deeply grateful. People who have walked the trail have expressed feeling transported, and shared that it is the first time since the pandemic escalated that they have been able to put it out of their minds. Some of the comments we have received include:

We felt the beauty and wonder of the time, place, and artistry of this creation. The walk is a masterpiece.

Amazing, inspiring.

What an awesome experience! I don't know where to begin - I'll never hear that music the same way again, and I've never experienced the forest and its noises, silence, and

movement in that way before.

While in the forest I think I forgot about the pandemic for the first time since it started…which is really saying something.

More information about the Beethoven Walks, and how to download apps with specifically-programmed music associated with each trail, are here.